The married are happier and more satisfied with their lives than the unmarried (Verbakel, 2012; Gove et al., 1990). Yet, as divorce and cohabitation increase, we may be facing a “retreat from marriage” (Cherlin, 2004). Besides, the life satisfaction advantage of being married (i.e., the difference between the average life satisfaction of married and unmarried people) has decreased over time in the US (Glenn & Weaver, 1988). Does this mean that marriage in contemporary societies has become less advantageous than in the past?

Over the past decades, another societal change has taken place: men and women have started to allocate their time more similarly than in the past (Bianchi et al., 2000), and the employment of women, even those with small children, has become widely accepted in most developed countries (Brewster & Rindfuss, 2000). Specialization, defined as the gendered division of tasks within married couples between the labor market (typically assigned to men) and household work (typically performed by women) has declined overall. And there are reasons to believe that the declining gender specialization within marriage reduces the comparative advantage of being married. First, it may directly lower the well-being of married couples (Becker, 1981). Second, the technological progress in household appliances and the greater availability of goods and services which replace household production may have improved the living conditions (especially) of the unmarried. Third, where gender specialization is strong, other social institutions (e.g., welfare provision) may be targeted to the advantage of specializing couples. Finally, the values change that accompanied the Second Demographic Transition (Lesthaeghe, 2010) might have decreased the life satisfaction advantage of being married.

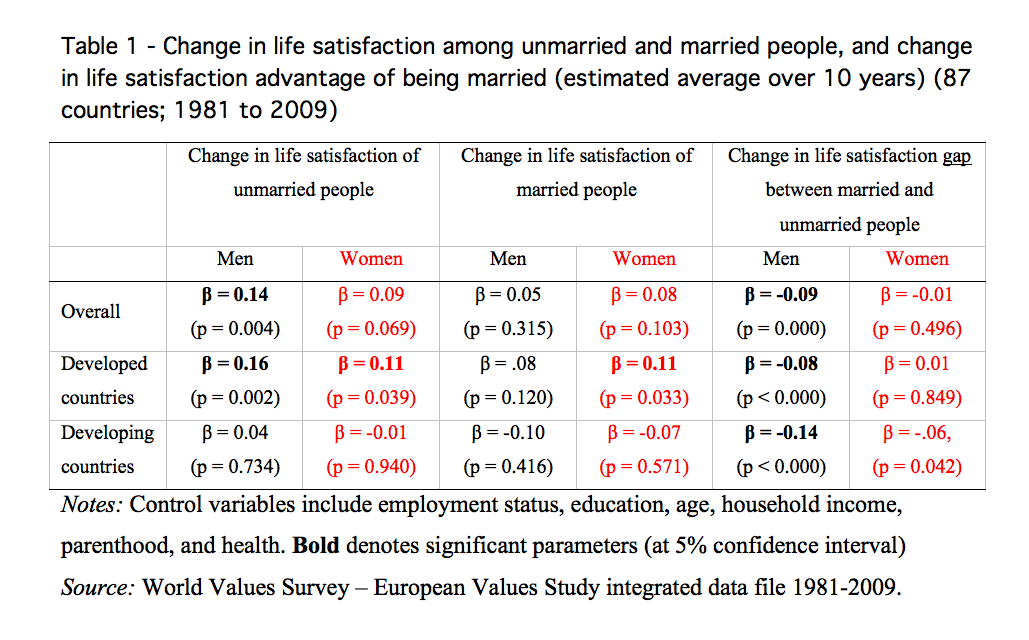

In a recent study (Mikucka, 2016) I tested two things. First, whether the life satisfaction advantage of being married has declined all over the world, as it has in the US. And, second, whether the change in the life satisfaction advantage of being married is related to the declining gender specialization at societal level. The data come from the integrated data set of World Values Survey and European Values Study for 87 countries for the period 1981-2009.

Does marriage still make people happy?

Over the years 1981-2009, the life satisfaction advantage of being married declined for men but not for women. More precisely, the life satisfaction gap between married and unmarried men declined on average from 0.54 to 0.28 (on a scale from 0 to 10). This decline resulted from the increasing life satisfaction of unmarried men, and the constant life satisfaction of married men. The average life satisfaction of both married and unmarried women remained unchanged, and so did the average gap between the two groups: 0.38 in 1981 and 0.36 in 2009 (Table 1).

The role of gender specialization

The decreasing life satisfaction advantage of being married among men was not correlated with (and, therefore, cannot be explained by) the changes in gender specialization that took place at the same time in those 87 countries.

However, if we restrict the analysis to the developed countries, we note that the correlation is absent for the married (i.e., the declining gender specialization does not affect their life satisfaction), but it is present, and negative, for the unmarried, i.e., their well-being tended to increase when contextual specialization declined. This suggests that the declining contextual gender specialization did not erode the life satisfaction of married couples, but created better conditions for single people and unmarried couples.

Marriage, happiness, and the social context

The study also looked at macro-factors related to the life satisfaction advantage of being married. Among various factors considered, two played a major role. First, economic growth correlates with the life satisfaction advantage of being married. This suggests that in terms of life satisfaction, married people benefit from improving economic conditions more than unmarried people. This is consistent with research showing that economic hardship affects the well-being of married people (Rogers and DeBoer, 2001) in particular. Additionally, growing GDP per capita plausibly frees people from the need to marry or to tolerate bad marriages.

The divorce rate also proved to be a statistically significant predictor: an increasing divorce rate positively correlates with the life satisfaction of both married and unmarried people. This result is consistent with previous studies suggesting that easier divorce allows people to dissolve unhappy and abusive marriages (Stevenson & Wolfers, 2006).

Concluding remarks

In short, gender specialization does not seem to lead to increased well-being of married people. And policies which attempt to strengthen the institution of marriage by creating incentives for gender-specialized division of work (e.g. tax systems that penalize dual-earner couples, or longer childcare leave for women) may not be effective tools for increasing the well-being of marriages.

Second, this analysis suggests that being married offers a source of life satisfaction advantage other than gender specialization. The specialization theory presents marriage as an arrangement that allows individuals to benefit from an exchange of productive skills that raises total household production above the sum of what each spouse could obtain independently: in other words, marriage is good for economic reasons. This study suggests, instead, that the well-being advantages of marriage are greater not under the conditions of economic necessity, but in conditions of free choice. This interpretation is consistent with the literature addressing the transformation of contemporary marriage from an arrangement that satisfies basic practical needs to an institution that helps to achieve personal accomplishment and self-fulfillment.

References:

Becker, G. S. (1981). A Treatise on the Family (No. beck81-1). National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. doi: 10.2307/1973663

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is Anyone Doing the Housework? Trends in the Gender Division of Household Labor. Social Forces, 79(1), 191–228. doi: 10.2307/2675569

Brewster, K. L., & Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and Women’s Employment in Industrialized Nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.271

Cherlin, A. J. (2004). The Deinstitutionalization of American Marriage. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(4), 848–861. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00058.x

Glenn, N. D., & Weaver, C. N. (1988). The Changing Relationship of Marital Status to Reported Happiness. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 317–324. doi: 10.2307/351999

Gove, W. R., Style, C. B., & Hughes, M. (1990). The Effect of Marriage on the Well-Being of Adults. A Theoretical Analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 11(1), 4–35. doi: 10.1177/019251390011001002

Lesthaeghe, R. (2010). The Unfolding Story of the Second Demographic Transition. Population and Development Review, 36(2), 211-251. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2010.00328.x

Mikucka, M. (2016). The life satisfaction advantage of being married and gender specialization. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78 (3), 759-779. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12290

Rogers, S. J., & DeBoer, D. D. (2001). Changes in Wives’ Income: Effects on Marital Happiness, Psychological Well-Being, and the Risk of Divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 458–472. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00458.x

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2006). Bargaining in the shadow of the Law: Divorce Laws and Family Distress. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(1), 267–288. doi: 10.1162/003355306776083572

Verbakel, E. (2012). Subjective Well-Being by Partnership Status and its Dependence on the Normative Climate. European Journal of Population/Revue Européenne de Démographie, 28(2), 205–232. doi: 10.1007/s10680-012-9257-2