Employment and childbearing are important stages in a woman’s life course. Their relationship is influenced not only by individual characteristics, but also by the socio-economic and institutional context. Availability of childcare services, flexible working hours, and paid leave with job protection after childbirth help women to balance work and family life (OECD 2011). If these social policies are generous enough, both female employment and fertility can be (relatively) high; conversely, a lack of these policies may depress both of them (Brewster and Rindfuss 2000; OECD 2007). Economic (un)certainty may also play an important role. In the face of economic upheavals, some women might give priority to their labor market roles and refrain from having a child, while others might see an opportunity to have a child when the job market becomes sluggish (Macunovich 1996).

Socio-economic and institutional context of South Korea

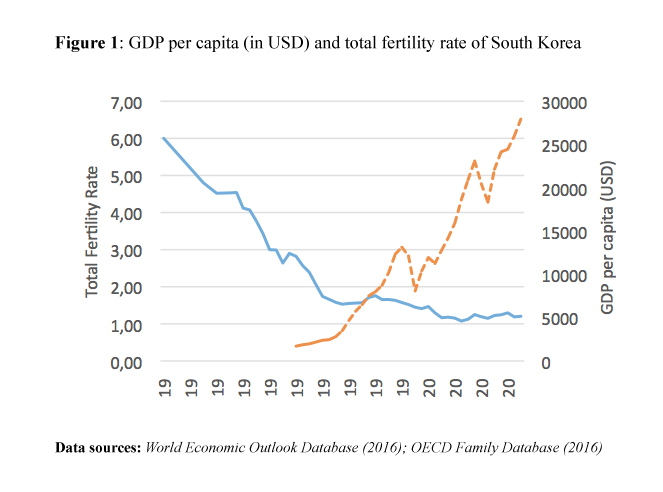

The economic growth of South Korea (or Korea) over the past few decades has been remarkable. Figure 1 shows that Korea’s GDP per capita increased rapidly from the early 1980s to the late 1990s. The rising trend was interrupted in 1997 by the sudden onset of the Asian Financial Crisis. It was not until 2002 that the country’s economic health was restored. Thereafter, its economy pursued its growth until 2008, when Korea was hit by another wave of economic recession. Conversely, Korea’s fertility level experienced a sharp decline over the same period. Its total fertility rate (TFR) plummeted from 6 children per woman in 1960 to 1.30 in 2001 (Ma 2013), possibly because of the country’s very effective family planning program, initiated in 1962 and abolished in 1989 (Choe and Retherford 2009). Korea’s progress in social policy development has been rather slow, however. At present, childcare provision is insufficient, opportunities for working flexible hours are limited, and only women with good labor market standing benefit from job-protected maternity/parental leave (Ma 2014).

How, then, do Korean women juggle work and family life?

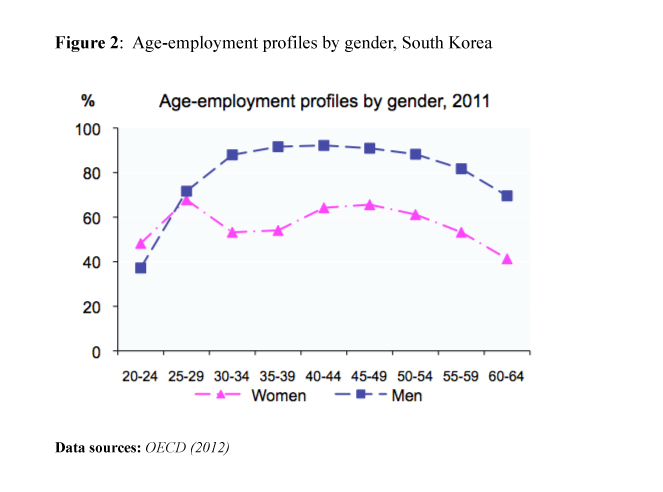

Among OECD countries, Korea ranks among the lowest for public spending on family benefits, including maternity and parental leave (OECD 2016). The Korean welfare system follows a familistic principle. Families follow a conservative pattern in terms of household chores and gender roles. Men act as the main breadwinner, and women as the primary caregiver. Korean women adopt a distinct strategy to reconcile work and family life (Figure 2). Most often, they work before marriage, leave the labor market during childbearing ages, and return to the labor market when the household needs them less. In other words, Korean women make a choice between work and family responsibilities. When they opt for one, they forgo the other.

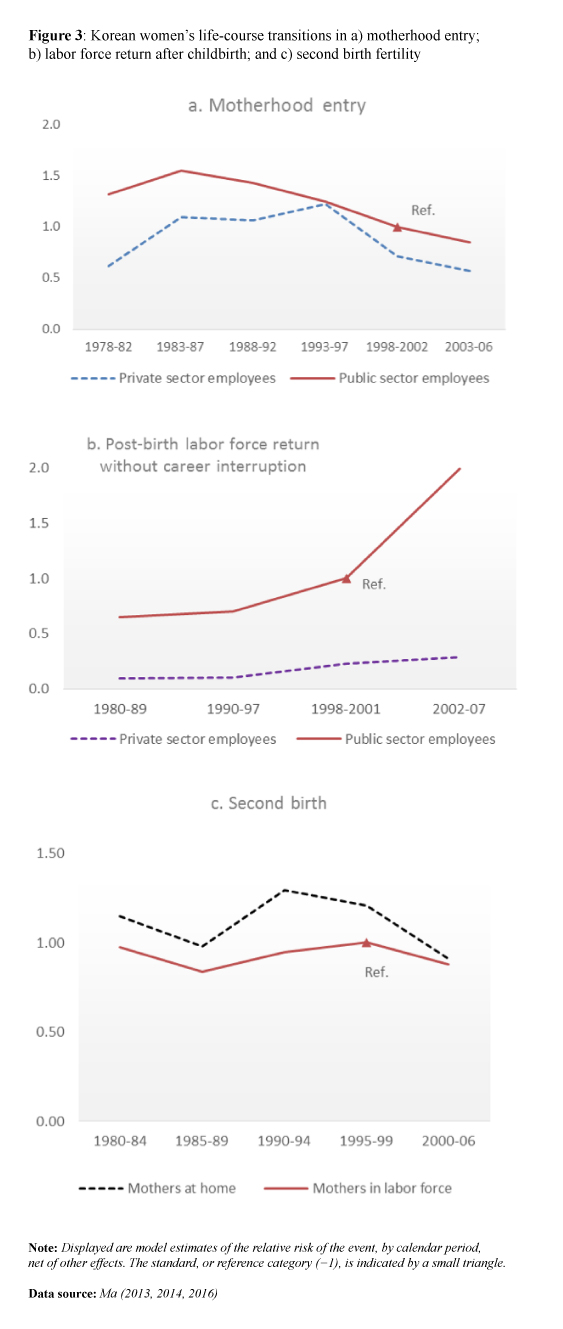

Obviously, this affects the relationship between employment and fertility in Korea. Ma (2013) shows that, traditionally, Korean women would leave the labor market before conceiving their first child. Labor market exit is a signal of family formation and extension. However, since the 1990s, this practice has been increasingly challenged, and staying at work up to and during pregnancy has gained prevalence. Among wage earners, women with stable employment positions are more likely to become a mother than those with irregular employment positions. For example, women employed in the public sector have had a higher likelihood of entering motherhood than private sector employees in the past 30 years or so (Figure 3a). This underlies the importance of employment stability for becoming a mother. Indeed, women with irregular jobs are sensitive to changes in the business cycle: they are more likely to become a mother during periods of economic growth, and less likely to do so during an economic downturn.

Women with good labor market standing, such as those with long work experience, public sector positions, high occupational status, or high income are more likely to resume employment after childbirth without career interruption (Figure 3b) (Ma 2014). Nonetheless, a considerable number of women (80%) shift to homemaking when becoming a mother. About 15% of these return to the labor force after a break of less than three years, 25% return when the youngest child turns three years or more and needs less attention, and the rest (60%) do not return at all. A career interruption of more than three years due to childbirth drastically curtails women’s probability of ever returning to the labor market. The Asian financial crisis in 1997 triggered a noticeable change in women’s post-birth labor force return behavior. To cope with the financial challenges, women became more strongly attached to the labor force than before. Mothers providing care at home tried to (re-)enter the labor market, even if the jobs that they could get were overwhelmingly of low status, below that they had enjoyed prior to childbirth (Ma 2014).

One-child mothers who are active in the labor force are significantly less likely to have a second child than homemakers (Figure 3c). Among working mothers, the propensity to have a second child is 26% higher for those with high occupational status than for elementary workers. In addition, it is particularly noteworthy that in a conservative society like South Korea, where the breadwinner-caregiver family model persists, the maintenance of the two-child norm depends above all on the husband’s potential to accumulate economic resources, rather than on the woman’s (Ma 2016).

What does the Korean story tell us?

The considerable proportion of women who become homemakers after childbirth and the lower second birth rates of mothers who are active in the labour force indicate that juggling the demands of work and family is difficult for women in contemporary Korea. Without sufficient policy support to help balance work and family responsibilities, they have to make a choice between the two. Nonetheless, the fact that women with better labour market standing (e.g., those employed in the public sector or with high occupational status) – the group that benefits most from Korea’s social policies – have a higher propensity to become mothers, are more likely to resume employment after childbirth without career interruption, and are relatively more likely to have a second child, may also shed some light on how Korea’s social policy should be oriented in the future. With better and more extended coverage, more women will have the freedom to decide on the number of children they want, and maintain their economic independence after becoming a mother.

References

Brewster, K. L. and Rindfuss, R. R. (2000). Fertility and women’s employment in industrialized nations. Annual Review of Sociology, 26:271-296.

Choe, M. K. and Retherford, R. D. (2009). The contribution of education to South Korea’s fertility decline to ‘Lowest-low’ level. Asian Population Studies, 5(3): 267-288.

Ma, L. (2013). Employment and motherhood entry in South Korea, 1978-2006. Population-E, 68(3): 419-446.

Ma, L. (2014). Economic crisis and women’s labor force return after childbirth: Evidence from South Korea. Demographic Research, 31(18): 511-552.

Ma, L. (2016). Female labor force participation and second birth rates in South Korea. Journal of Population Research, 33(2): 173-195.

Macunovich D. J. (1996). Relative income and price of time: Exploring their effects on US fertility and female labor force participation. Population and Development Review, 22(supp.): 223-257.

OECD (2007). Facing the Future: Korea’s Family, Pension and Health Policy Challenges, OECD, 89 p.

OECD (2011). Doing Better for Families, OECD, 275 p.

OECD (2012). OECD Labor Force Statistics Database, OECD.

OECD (2016). OECD Social Expenditure Database, OECD.