Holding Spanish students back a year: just how effective is it?

Repeating a school year is an ineffective pedagogical practice: it fails to improve the academic performance of those who are held back, and in some cases it may even make things worse.

In a country like Spain where ‘grade retention’ is the main tool for addressing underachievement, Álvaro Choi, María Gil, Mauro Mediavilla and Javier Valbuena’s empirical findings highlight the need to consider alternative educational policies.

A third of Spanish students will have repeated a year by the end of their compulsory schooling

The pedagogical practice of ‘grade retention’, or making a student repeat a school year because of poor grades, is the subject of much debate among academics and educationalists alike. Although recent empirical evidence tends to suggest it does little to improve students’ results (continuity, performance and graduation), many countries continue to implement this measure (Allen et al., 2009; Manacorda, 2012). As Spain is among the “top” countries in terms of “students’ retention”, we decided to analyse the effectiveness of grade retention in improving the school performance of Spanish students (Choi et al., 2018a,b).

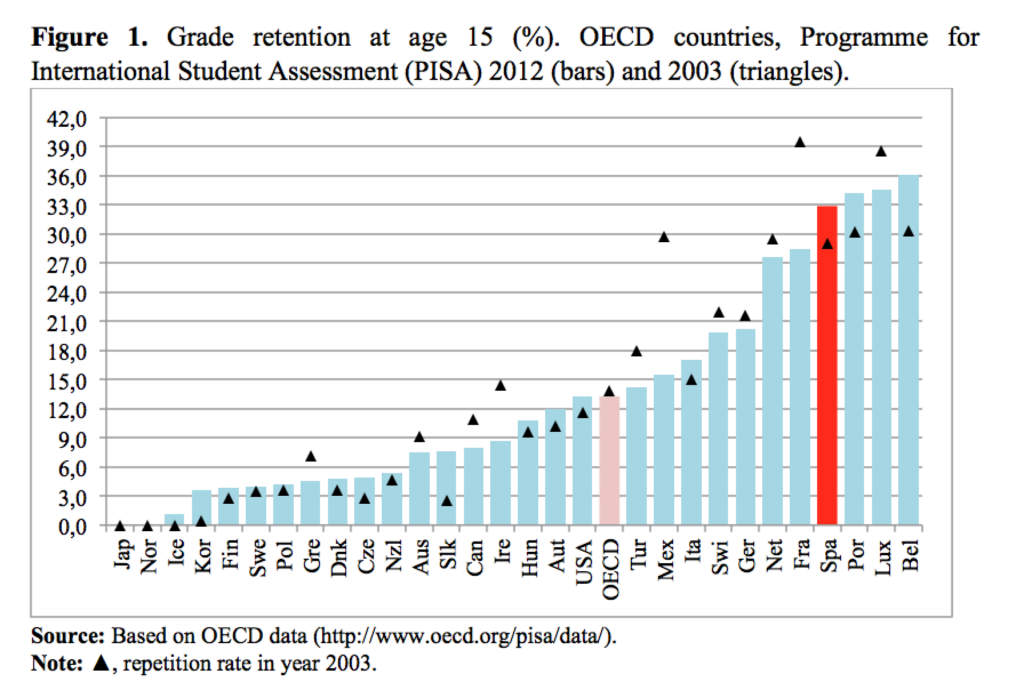

Among developed countries, the use of grade retention as an educational policy varies greatly. Drawing on OECD/PISA data, Figure 1 shows how rates of grade repetition varied for a representative group of countries in 2003 and 2012, for students aged 15 years (OECD, 2014). While in countries like Japan and Norway no students were held back, because they implement the alternative policy of automatic ‘promotion’, in Belgium, Luxembourg, Portugal, Spain, France and the Netherlands, retention rates were surprisingly high. In Spain, the percentage of students who had to repeat at least one grade by the end of their compulsory education increased across the period, affecting almost a third of students in 2012.

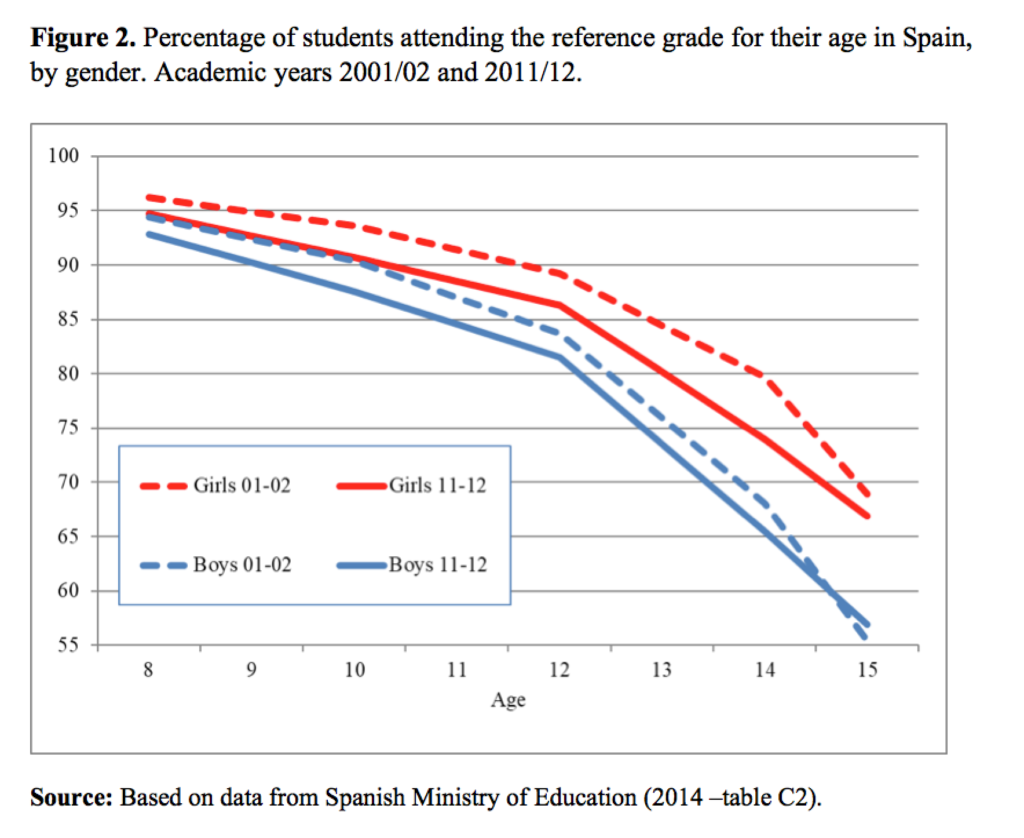

Figure 2 shows that in Spain most students tend to be held back during compulsory secondary education. In other words, it is a policy that primarily affects students between the ages of 12 and 16, and boys are more likely to repeat a year, relative to girls.

Does being held back serve to motivate or does it simply stigmatise students?

The main arguments in favour of grade retention are grounded in the belief that while the policy sanctions the students’ behaviour, it also acts as a motivator: first, it deters underachievement and helps foster greater effort; and, second, it gives students more time to consolidate their learning and mature. The policy’s detractors, however, claim that students who are held back do not improve and that many, in fact, get worse results the second time around. They argue that students who have repeated not only need to retake subjects they have already passed but, in being separated from their classmates, they suffer the stigma of being labelled not especially bright, with the harmful effects this can have for their self-esteem and motivation. The upshot is that grade retention can result in problems of discipline for schools. What’s more, the policy has a considerable impact on the public funds. In Spain, the evidence is scant and inconclusive, primarily because of the major limitations of the country’s databases (most notably the lack of longitudinal data).

Who benefits from being made to repeat a school year? Certainly, not the students.

An initial descriptive examination of the data indicates that, in Spanish primary schools, those who are held back a year have worse academic results and that, by the end of secondary school, the gap between the two groups has increased substantially. Not unsurprisingly, in Spain, boys are held back more frequently than girls. Similarly, a higher percentage of students having to repeat a school year is found among those living in single-parent families, in households of low socioeconomic status (SES) and among first- and second-generation immigrants, all of whom are at greater risk of school failure.

The empirical results indicate that grade retention – having first considered a student’s academic performance in primary education and several other individual and parental control variables – has a decidedly negative impact. What’s more, the magnitude of this impact increases by more than 60% when a student has been held back two or more grades, which indicates that the negative effect is also cumulative.

It is equally interesting to observe that grade retention affects more severely the best students among the low achievers (greater disappointment, here?), which clearly questions a one-size-fits-all policy for students performing below the required level. Finally, our results show how differences in academic performance based on socioeconomic factors become more marked between primary and secondary schooling. This highlights the importance of identifying students with these characteristics at an early age, given their greater risk of school failure, so as to provide them with more specific mechanisms of support.

In short, our analysis indicates that grade retention is an ineffective pedagogical practice. What’s more, in the short term, it has clearly negative effects on a student’s academic performance and, moreover, this effect is heterogeneous by socioeconomic status (SES) and previous academic achievement. In a country like Spain, where grade retention is the main tool for addressing underachievement (despite being described as an ‘exceptional measure’ in the state education act), our empirical findings highlight the urgent need to consider alternative educational policies. Priority needs to be given to the establishment of mechanisms that can identify students at risk of school failure during the initial stages of their education, and to the introduction of measures that guarantee support and specific services for underachieving students should they be automatically promoted to the next grade, such as remedial courses during the summer months. However, if Spain opts to continue with its policy of grade retention, schools and teachers should be careful not to apply it in a uniform fashion to all students.

References

Allen, C.S., Chen, Q., Willson, V.L. and Hughes, J.N. (2009). “Quality of Design

Moderates Effects of Grade Retention on Achievement: A Meta-Analytic, Multi-

Level Analysis”, Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 31.

Choi A., Gil M., Mediavilla M, Valbuena J. (2018a). “Predictors and Effects of Grade Repetition in Spain”, Revista de Economía Mundial/World Economy Journal, 48: 21-42.

Choi A., Gil M., Mediavilla M, Valbuena J. (2018b). “The evolution of educational inequalities in Spain: dynamic evidence from repeated cross-sections”. Social Indicators Research, 138(3): 853-872. DOI: 10.1007/s11205-017-1701-6

Manacorda, M. (2012). “The cost of grade retention”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 94, 596-606.

OECD (2014). PISA 2012 Results in Focus: What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know, OECD, Paris.

Source figure 2

http://www.oecd.org/pisa/data/