Educational consequences of parental divorce and death in Europe

Children and youngsters who experience parental divorce or parental death often attain lower levels of education than their peers, but the impact of these adverse events is far from uniform, as Carlijn Bussemakers, Gerbert Kraaykamp & Jochem Tolsma show. Educational losses tend to be greater for children of highly educated parents.

In a recent study, using data from the Generations and Gender Survey, a collection of European surveys on individual life-courses and family dynamics, we focused on people from 17 European countries and four birth cohorts (born between 1945 and 1984) to investigate the association between experiencing parental divorce or parental death and educational attainment.

Parental divorce: reduced reproduction of family resources

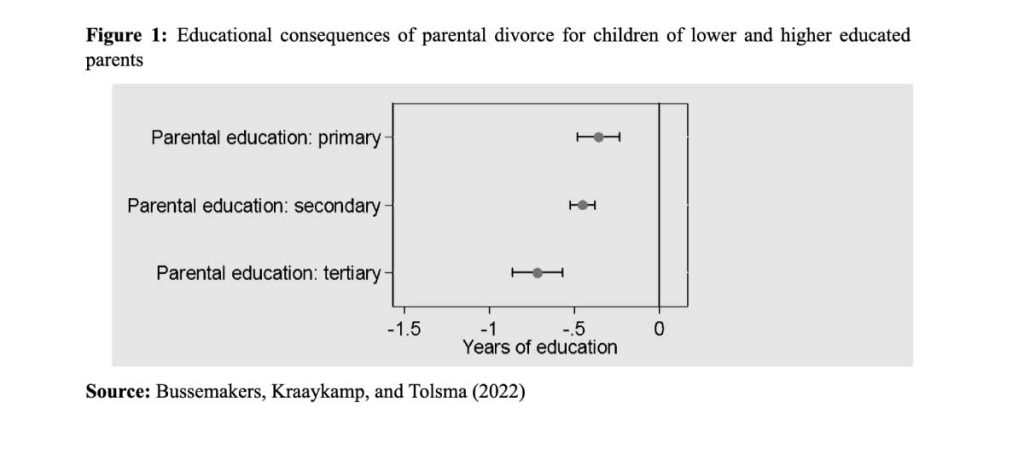

Experiencing parental divorce during childhood or youth negatively affects education, but the size of this impact depends on the parents’ level of education. For children of tertiary-educated parents, the impact of parental divorce is almost twice as large as for children of primary- and secondary-educated parents (Figure 1). This pattern holds across countries and is not affected by national factors such as selectivity of the educational system or divorce rate.

This phenomenon can be understood by what we call reduced reproduction of parental resources. Generally, higher educated parents use their resources to advance their children’s educational careers. Children benefit from their parents’ financial means (e.g., parents can afford extra tutoring for their children) as well as their cultural resources (e.g., parents stimulate children’s development by reading to them). In an earlier study on Dutch data, we showed that the transmission of cultural resources is hindered by adverse events such as parental divorce, because divorced parents tend to have less time and energy to promote their children’s development and educational attainment (Bussemakers and Kraaykamp 2020). This loss in resources is larger for children who “have more to lose”, that is children of highly educated parents (Bernardi and Radl 2014; Bussemakers and Kraaykamp 2020). These children not only experience the direct negative consequences of divorce, but also lose part of their socialisation advantage.

Parental death: national institutions as buffering factors

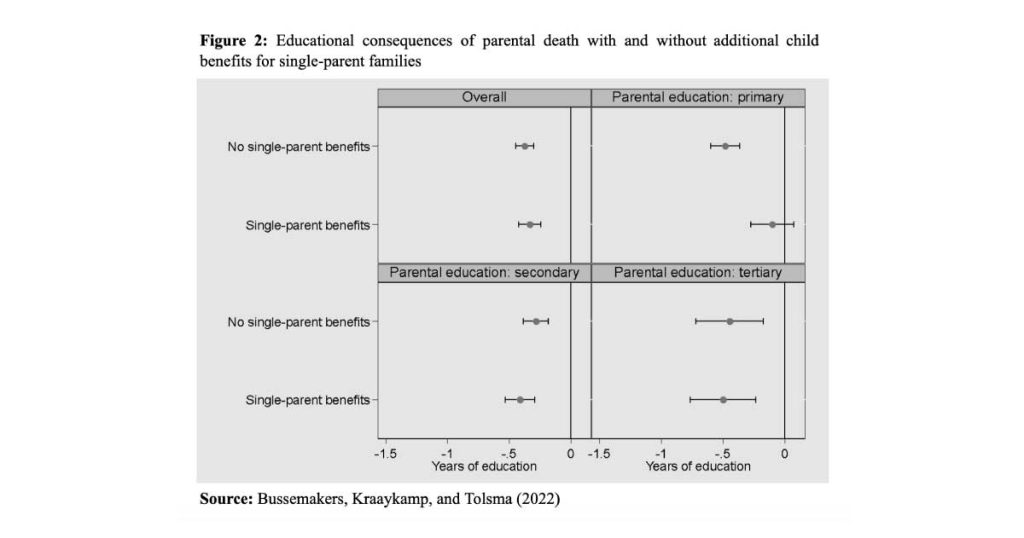

Parental death, instead, has a comparable impact for all children: those who experience the death of at least one of their parents during their youth “lose” about 0.35 years of education in all. This impact is not uniform across European countries, however. For children of lower educated parents, availability of family benefits and a less selective educational system function as buffers against the impact of parental death.

Figure 2 illustrates the role of family benefits, indicated by whether a country offers additional child benefits to single-parent families. When these benefits are available, children of lower educated parents do not attain lower levels of education when they experience parental death, compared to children of lower educated parents without this experience. This suggests that benefits can alleviate some of the problems faced by widowed, lower-educated parents, mitigating the disadvantage of their children (Hampden-Thompson 2013). Conversely, additional child benefits for single-parent families do not reduce the impact of parental death for children of secondary- and tertiary-educated parents.

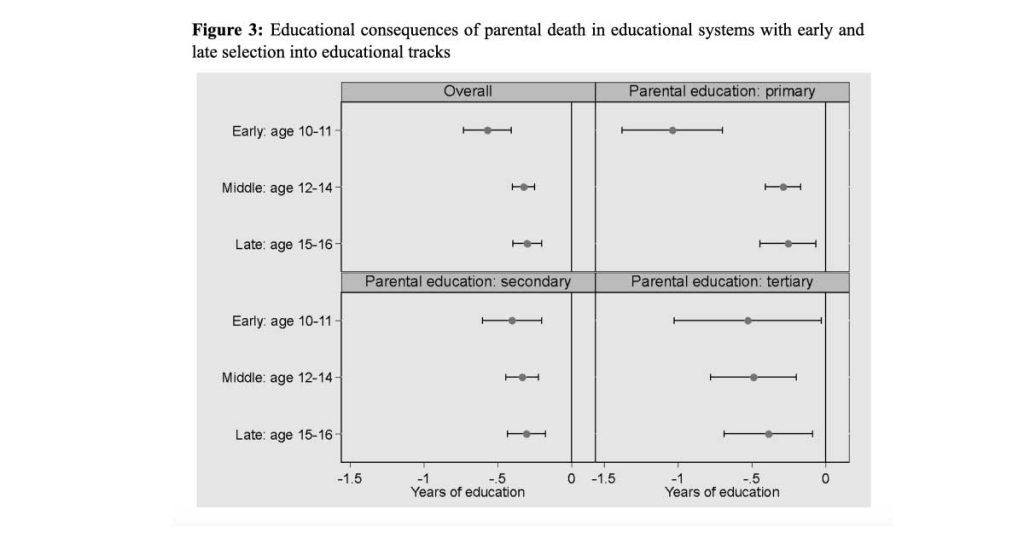

The educational system also plays an important role for children of lower-educated parents who experience parental death. Figure 3 illustrates the role of selectivity of the educational system, indicated by the age at which children are selected into different educational tracks. In systems where children are selected at a young age, children of lower educated parents face a much larger impact of parental death. Children of lower educated parents are generally more disadvantaged in more selective educational systems because they are often placed in “lower” educational tracks (Van de Werfhorst and Mijs 2010). Our results add that more selective systems accentuate this disadvantage for children who also experience parental death. This is in line with theories on cumulative disadvantage, which argue that negative experiences may reinforce each other (DiPrete and Eirich 2006). Such cumulative disadvantage is not found in educational systems where selection occurs at average or later children’s ages.

Conclusion

To understand the impact of parental divorce and parental death on children’s educational attainment, it is important to consider the context in which children grow up. Educational and welfare policies can help reduce the impact of parental death for the most disadvantaged group, namely children of lower-educated parents. Unfortunately, they provide less support for children of higher-educated parents and/or children who experience parental divorce. We also did not find a buffering role of parental resources for these groups. Instead, the relative impact of parental divorce is larger for children who have more parental resources to lose. In these cases, it becomes particularly important to look for other sources of support, such as teachers, health professionals and/or peers.

References

Bernardi, F. and Radl, J. (2014). The long-term consequences of parental divorce for children’s educational attainment. Demographic Research 30(61):1653–1680. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2014.30.61.

Bussemakers, C. and Kraaykamp, G. (2020). Youth adversity, parental resources and educational attainment: Contrasting a resilience and a reproduction perspective. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 67(February):100505. doi:10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100505.

Bussemakers, C., Kraaykamp, G., and Tolsma, J. (2022). Variation in the educational consequences of parental death and divorce: The role of family and country characteristics. Demographic Research 46:581–618. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2022.46.20.

DiPrete, T.A. and Eirich, G.M. (2006). Cumulative Advantage as a Mechanism for Inequality: A Review of Theoretical and Empirical Developments. Annual Review of Sociology 32(1):271–297. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.32.061604.123127.

Hampden-Thompson, G. (2013). Family policy, family structure, and children’s educational achievement. Social Science Research 42(3):804–817. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2013.01.005.

Van de Werfhorst, H.G. and Mijs, J.J.B. (2010). Achievement Inequality and the Institutional Structure of Educational Systems: A Comparative Perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 36(1):407–428. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102538.