Women’s economic empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa: what do we know?

The centrality of women’s economic empowerment in achieving the sustainable development goals has attracted high level policy interest. Data limitations impede knowledge of its extent in Africa. Demographic and health surveys can, however, be used to study it, says Eunice Williams. She finds that women’s economic empowerment is low but variable within the region, and countries can be divided into five typologies.

Introduction

In 2015, United Nations member states adopted Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) promising to leave no one behind. Gender equality and empowerment of women and girls is not only a stand-alone goal (SDG 5), but also a cross-cutting issue in several other goals (United Nations, 2015). In 2016, women’s economic empowerment, or WEE, was identified as the cornerstone for achieving the SDGs, and a requirement for poverty eradication (United Nations, 2016). Despite its policy relevance, there is inadequate evidence to track its progress.

According to UNECA’s Africa 2020 SDGs Progress Dashboard, indicators for the fifth goal (SDGs 5) are insufficient to provide the full picture of progress due to data gaps (Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2020). Since women’s economic empowerment is central for sustainable and gender transformative development, we need to find innovative ways of using existing data to track its progress. Cross-sectional household surveys already conducted in most African countries could be the answer to this challenge.

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) provide standardised cross-sectional data at the household level and are widely available. They even include an empowerment module. In a recently published study, we analysed these data in 33 African countries constructing an economic empowerment score for each one (Williams et al, 2022). The score takes into account women’s post-primary education attainment, employment, income earning, decision-making abilities on use of own or partner’s income, and land ownership.

Women’s economic empowerment is low but varies by country

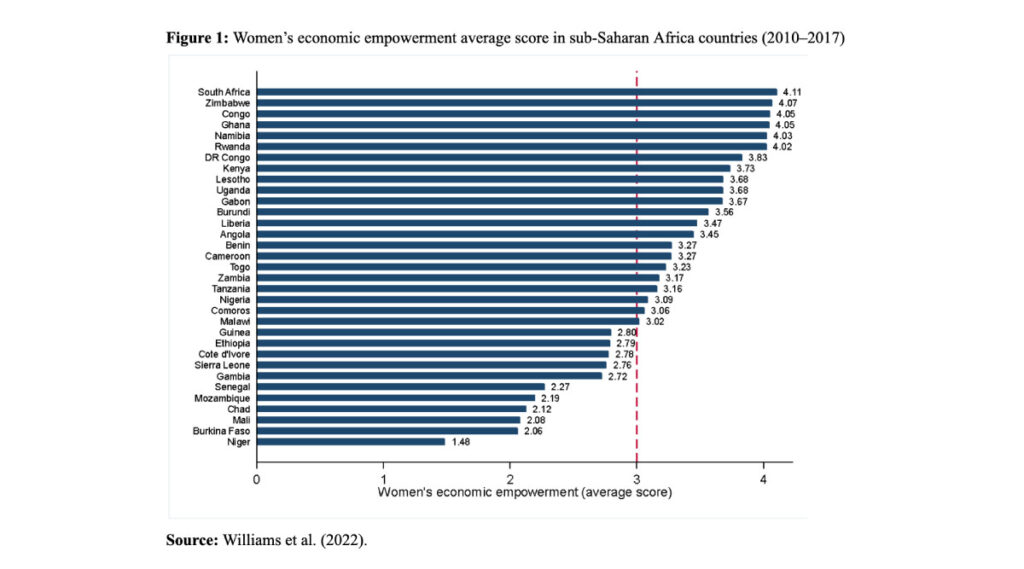

Women’s economic empowerment is at low levels in Africa: 3 out of 9 on average (Figure 1). The lowest level we found was 1.5 in Niger and the highest was 4.1 in South Africa.

These low levels of economic empowerment could be explained by various barriers preventing women from accessing and controlling economic opportunities and assets, in addition to a heavy burden of unpaid care work. For example, underlying socio-cultural norms that dictate unequal gender relations and attitudes likely hold back women’s agency and curtail their empowerment. Gender discrimination in the labour market leads to a lower earning potential among women compared to men. In addition, in some cases, even if women own land, they may not be able to access agricultural production assets or produce markets because patriarchal societies limit their economic independence.

Similarities and differences in women’s economic empowerment across countries

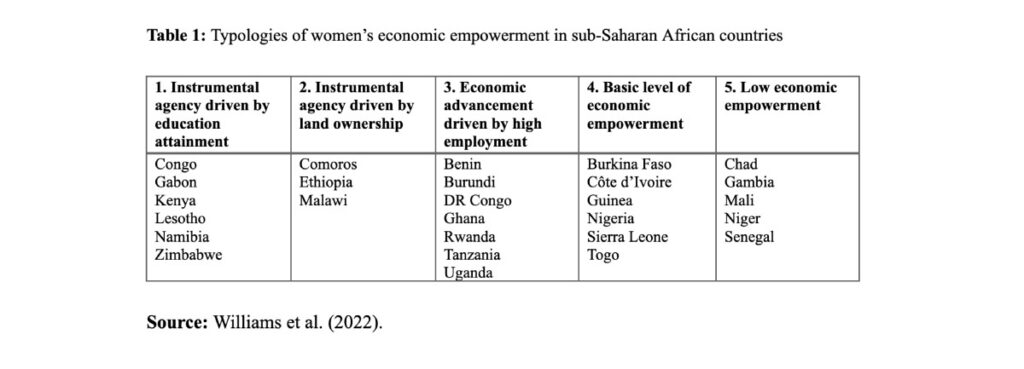

The observed levels of women’s economic empowerment are closely linked to three key factors: educational attainment, employment, and land ownership. The various combinations of the presence or absence of the above three factors result in different types of women’s economic empowerment that vary across countries. We identified five different typologies of women’s economic empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa countries as shown in Table 1:

1) instrumental agency explained by high educational attainment;

2) instrumental agency explained by land ownership;

3) individual economic advancement explained by high employment rates;

4) basic level economic empowerment; and

5) low-level economic empowerment, where the three factors are, on average, almost non-existent.

Instrumental agency refers to exercising one’s capabilities and choice through influence or control over decisions within the household, while economic advancement entails economic gain and success, and is measured using productivity and earnings in terms of increased income, savings or business profits. These five typologies show the main “drivers” of observed women’s economic empowerment at the household level for each set of countries, highlighting the areas that should be improved to further enhance economic empowerment.

Countries in the first category have the highest WEE score, driven by high post-primary education attainment, which contributes to both autonomy and influence on economic decisions at household level. In the second category, land ownership increases women’s bargaining power, allowing women to participate more fully in household economic decisions. Countries in the third category have high levels of employment. However, other than providing income, high employment has not translated to increased autonomy and decision-making at the household level, mainly because women tend to work in low-quality jobs or small-scale enterprises. The fourth category consist of countries where land ownership and employment contribute to some economic empowerment, but not substantially, while education attainment is generally low. The last category consists of countries with limited evidence of economic empowerment based on the three identified components.

Six countries included in Figure 1 are missing in Table 1. Angola, Cameroon, Liberia and South Africa had missing data on land ownership, and thus were dropped from the analysis (Principal Component Analysis ‒ PCA) that produced Table 1. Mozambique, and Zambia were excluded because the WEE measurement indicators included in this study could not explain the factors resulting in the observed instrumental agency.

Ways to improve women’s economic empowerment

As the United Nations General Assembly convenes this year (2022) to assess the progress made in development, questions around data and research gaps will surely arise. The potential of cross-sectional surveys in tracking the progress of women’s economic empowerment should not be downplayed. Admittedly, the economic empowerment indicators included in the DHS data are limited, and more could, and should, be done to broaden their scope. Until this happens, however, the DHS is a good starting point, and its data, if properly treated, can provide timely evidence on the extent of women’s economic empowerment in Africa, its drivers, and barriers.

On this basis, programme interventions and strategies can be built to leap-frog sub-Saharan African countries towards their SDG targets and other development goals, including those of the wider African Union development agenda (Agenda 2063).

References

Sustainable Development Goals Center for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network (2020). Africa SDG Index and Dashboards Report 2020. Kigali and New York, SDG Center for Africa and Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, United Nations.

United Nations (2016). Leave no one behind: A call to action for gender equality and women’s economic empowerment: Report of the UN Secretary- Generals high-level panel on women economic empowerment. New York, USA, UN Secretary general secretariat.

Williams E., Väisänen H., Padmadas S. (2022). Women’s economic empowerment in sub-Saharan Africa: Evidence from cross-national population data. Demographic Research 47(15): 415‒452.