Unintended and sooner-than-intended childbearing in Eastern and Western Europe

Examining two waves of a panel survey, Zuzanna Brzozowska, Isabella Buber-Ennser and Bernhard Riederer find evidence that women and men in post-socialist countries more often have a child they planned for later or not at all than in other European countries. The East-West divide is largely driven by differences in the anticipated cost of having a (further) child in the East and West.

Past research has shown that women and men in post-socialist countries fulfil their intention to have a child less often than elsewhere in Europe (Kapitány and Spéder 2012; Riederer and Buber-Ennser 2019). Does a similar geographical pattern exist for the realisation of intentions to postpone or forego (further) childbearing?

In a recent paper, we analysed two panel waves of the Generations and Gender Survey (GGS) in six countries (in brackets the years when the waves were conducted): Bulgaria (2004 and 2007), Hungary (2004/05 and 2008/09) and Poland (2010/11 and 2014/15) in Eastern Europe; Austria (2008/09 and 2012/13), France (2005 and 2008) and Italy (2003 and 2007) in Western Europe. Our analysis accounts for the different intervals between waves in the countries included (see Brzozowska et al. 2021). Based on the short- and long-term fertility intentions expressed by potential parents at the first survey wave, we classified the births occurring between the waves as:

• Intended: children born to parents who had reported wanting them;

• Sooner-than-intended: children born to parents who had reported intending to postpone (further) childbearing;

• Unintended: children born to parents who had reported intending to forego (further) childbearing.

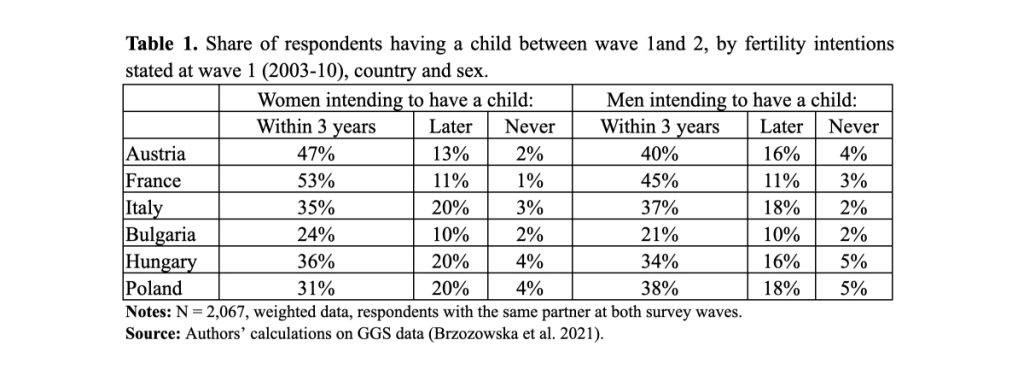

Table 1 shows how many respondents had a child between the waves depending on their fertility intentions stated at wave one. Note that GGS data do not indicate whether births were desired at the time of conception. Therefore, not all the births that we classified as unintended or sooner-than-intended are actually unwanted or mistimed, respectively, because some may have occurred following a change in a respondent’s childbearing intentions. To minimise this bias, we only included respondents who had the same partner at both survey waves.

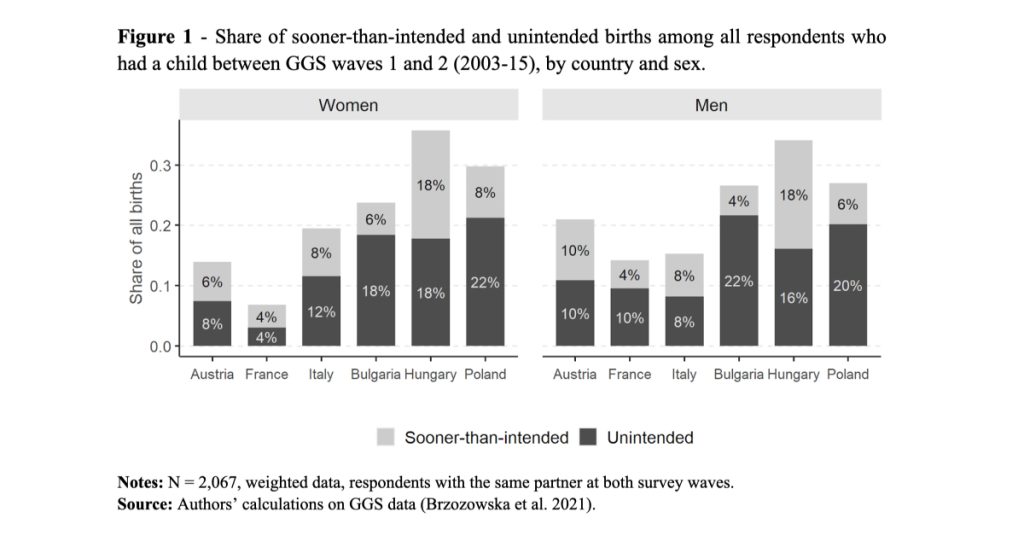

The geography of sooner-than-intended and unintended births

Among respondents who had a child between the survey waves, around 10% in the West and 30% in the East experienced an unintended or a sooner-than-intended birth, with the lowest value (8%) among women in France, and the highest (36%) among women in Hungary (Figure 1). The East-West divide is largely driven by the share of unintended births, which is clearly higher in post-socialist countries.

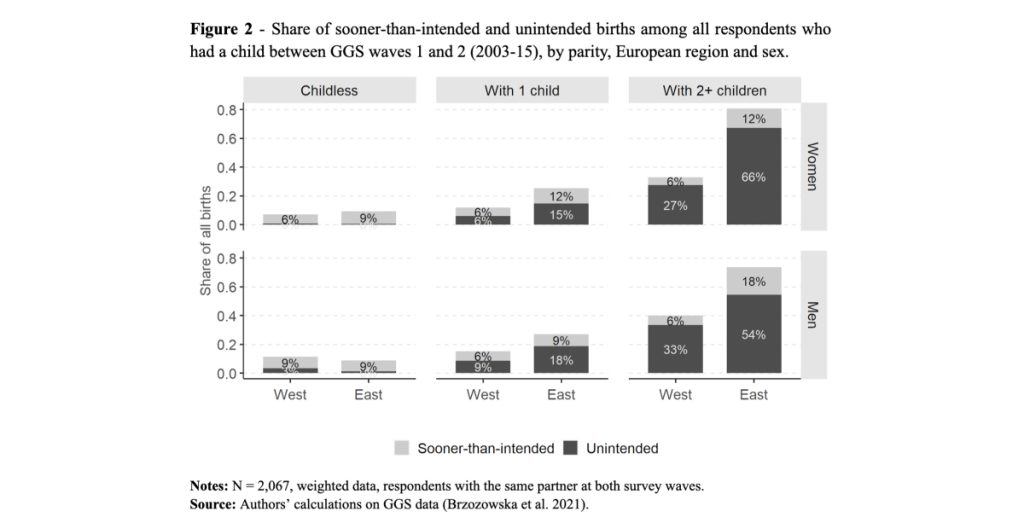

The group that fuels the geographical pattern are parents of two or more children (Figure 2). In the East, 66% of births to mothers and 54% of births to fathers with at least two children were unintended, versus only 27% and 33%, respectively, in the West. Note that in both parts of Europe, births to parents who already have two or more children represent the lion’s share of all unintended births: almost two-thirds among women and one half among men (results not shown). This geographic pattern can also be observed for sooner-than-intended births to parents of two or more children. The East-West divide weakens for second births and disappears for first ones.

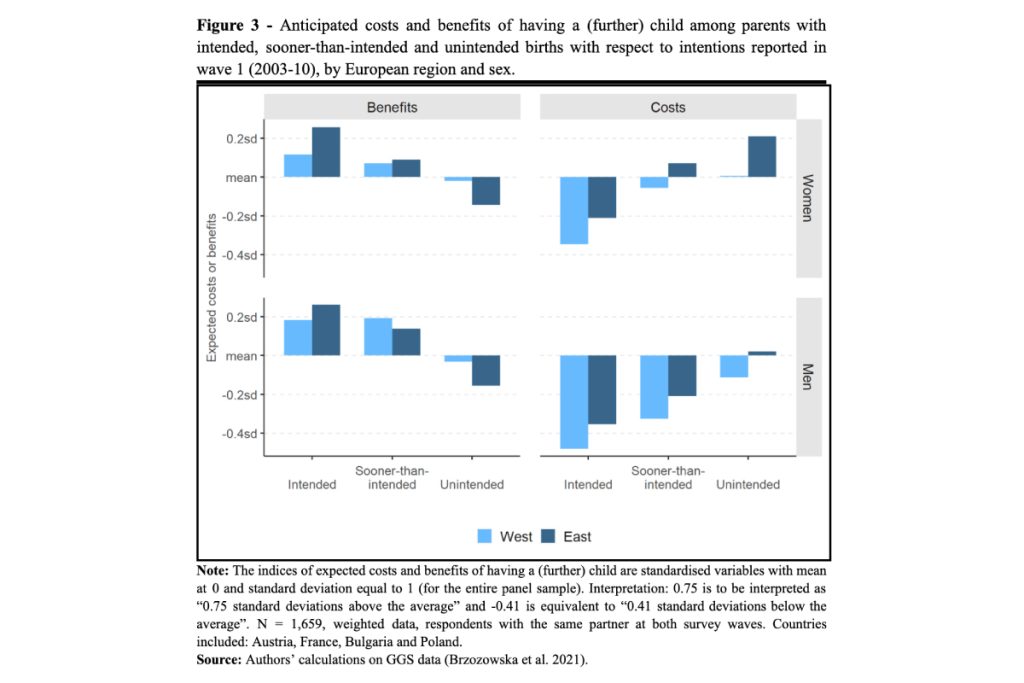

A geographic divide largely explained by anticipated cost

In four of the analysed countries (Austria, France, Bulgaria and Poland) respondents were asked at wave one about the anticipated costs and benefits of having a child. Our analysis shows that these are among the main factors associated with a sooner-than-intended or an unintended birth rather than an intended one. For women and men in all four countries, the anticipated costs are lowest among parents with intended births and highest among parents with unintended births (Figure 3). The benefits display a reverse pattern. In all three groups of parents, Western Europeans systematically expect lower costs than Eastern Europeans.

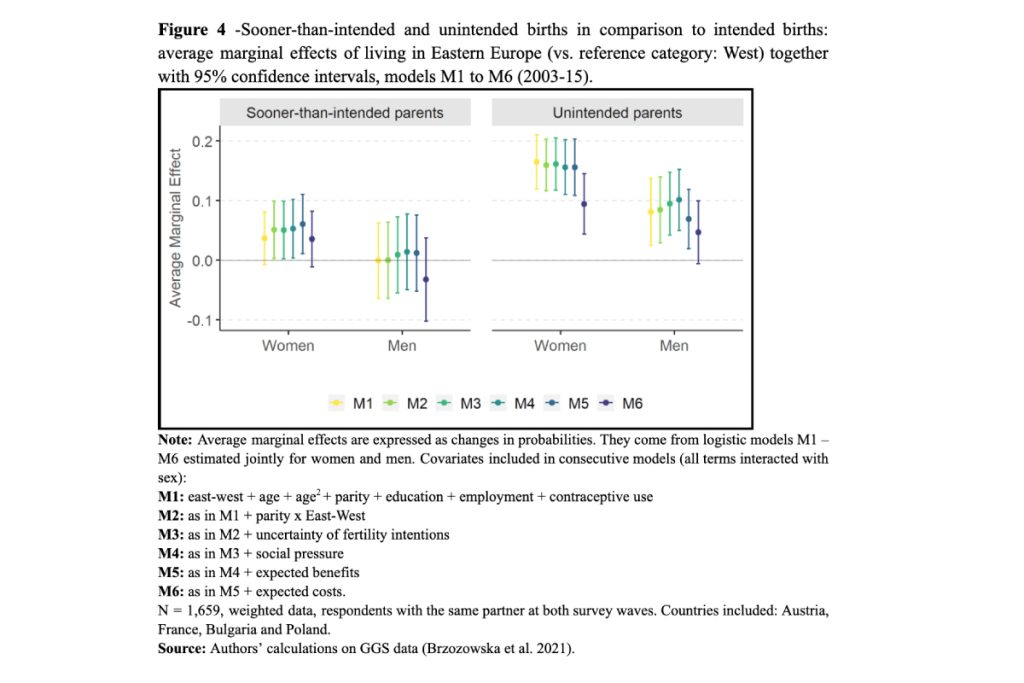

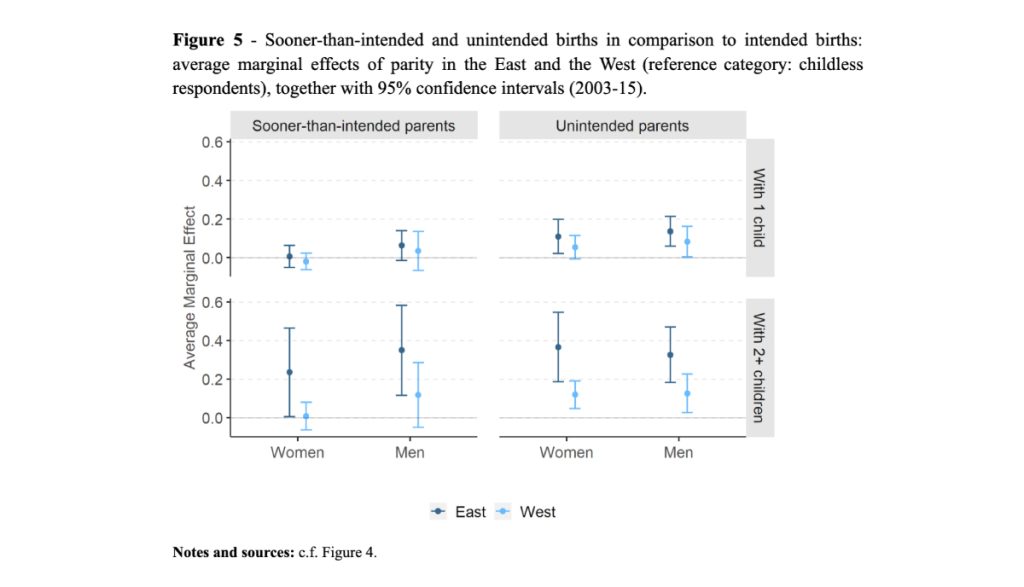

Further analysis, in which several of the respondents’ characteristics are controlled for, demonstrates that the geographical pattern weakens (for women) or entirely disappears (for men) when anticipated costs of having a child are considered (Figure 4, model M6 as compared to models M1 – M5). At the same time, however, the East-West difference in the effect of parity (i.e. the number of children one already has) remains (Figure 5). In the West, the probability of having a child sooner-than-intended does not depend on parity, but in the East it is 20 percentage points higher among women and 30 points higher among men for parents of at least two children than for childless respondents. For parents with unintended births, parity plays an important role both in Western and Eastern Europe. The effect is particularly strong for parity 2+: having two or more children rather than none increases the probability of experiencing an unintended birth by more than 10 percentage points in the West and by more than 30 points in the East for both sexes.

Concluding remarks

To a large extent, the East-West divide in the share of unintended births simply reflects East-West differences in the anticipated costs of having a (further) child. Women and men in post-socialist countries expect costs to be higher probably because, on average, they face tougher socioeconomic conditions, such as cramped housing, a scarcity of part-time jobs, a shortage of childcare places for under-threes, little support from the state (the GGS was conducted before large-scale family social programs were introduced in Poland and Hungary; see Sobotka et al. 2019) and relatively low wages. The labour market tends to have relatively weak protections for employees while the low levels of unemployment benefit provide only a thin safety net in case of job loss (European Commission 2018).

The fact that parents of two or more children are more likely to have an unintended birth may be a manifestation of the two-child norm (Sobotka and Beaujouan 2014). Individuals who would like to have more than two children but feel they lack the resources or the support to do so might report not intending to have an additional child and yet not be fully committed to that intention.

References

Brzozowska, Z., Buber-Ennser, I. & Riederer, B. (2021) Didn’t plan one but got one: unintended and sooner-than-intended parents in the east and the west of Europe. European Journal of Population 37(2): 727–767. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-021-09584-2

European Commission. (2018). Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2018. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Kapitány, B., & Spéder, Z. (2012). Realization, Postponement or Abandonment of Childbearing Intentions in Four European Countries. Population-E, 67(4): 599–629.

Riederer, B., & Buber-Ennser, I. (2019). Regional context and realization of fertility intentions: the role of the urban context. Regional Studies, 53(12): 1669–1679.

Sobotka, T., & Beaujouan, É. (2014). Two Is Best? The Persistence of a Two-Child Family Ideal in Europe. Population and Development Review, 40(3): 391–419. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00691.x

Sobotka, T., Matysiak, A., & Brzozowska, Z. (2019). Policy responses to low fertility: How effective are they? UNFPA Working Paper No. 1.