Growing old in a post-communist society. Who gets lonely in Poland and when?

Małgorzata Mikucka sheds new light on the loneliness of elderly people in Poland, focusing on the events and transitions that trigger this feeling. Weak social ties and a legacy of communism, may partly explain her results.

Now that increasing numbers of older adults live alone, the feeling of loneliness may become a serious societal issue when people age without close kin. Although strong social relationships, one of the ingredients of successful ageing, can be maintained by older adults, it is easier to have intimate relations with someone who lives under the same roof than to reach out to people living elsewhere.

The age-related dynamics of loneliness have been amply documented in Western Europe, but much less so in Eastern Europe. In the West, the older old (people aged 80 years or over, although the definition varies across societies) are disproportionally more lonely than the middle-aged, although this problem does not seem to affect the younger old (between around 60‒65 and 80 years; Hansen & Slagsvold, 2016).

In countries with strong family ties, such as those in the Mediterranean area, the elderly have frequent contacts with their families, but this helps them little, because they seem to expect more than people in Northern Europe. This explains why about 20% of people aged 65+ report persistent loneliness in Greece and Italy, but only 5% in Switzerland (Vozikaki et al., 2018). Like the Mediterranean region, Eastern Europe has particularly high levels of old-age loneliness, experienced “frequently” by as many as 34% of older adults in Ukraine, and 20% in Poland (Yang & Victor, 2011). More alarmingly, the increase in loneliness in Eastern Europe seems to start early, from age 30 years or so (Yang and Victor, 2011).

New evidence for Poland

In a recent study, I provided new longitudinal evidence on loneliness among older adults in Poland (Mikucka 2021). This phenomenon has rarely been studied in Central and Eastern Europe, especially using longitudinal nationally representative data (see, however, the PolSenior project by Błędowski et al., 2011). Data were drawn from the POLPAN study (http://polpan.org/en/), a panel survey initiated in 1988, which followed respondents every five years until 2018. In my analysis, I used data collected in 2008, 2013, and 2018, with the age intervals 60 to 74 years for the younger old and 75 and over for the older old.

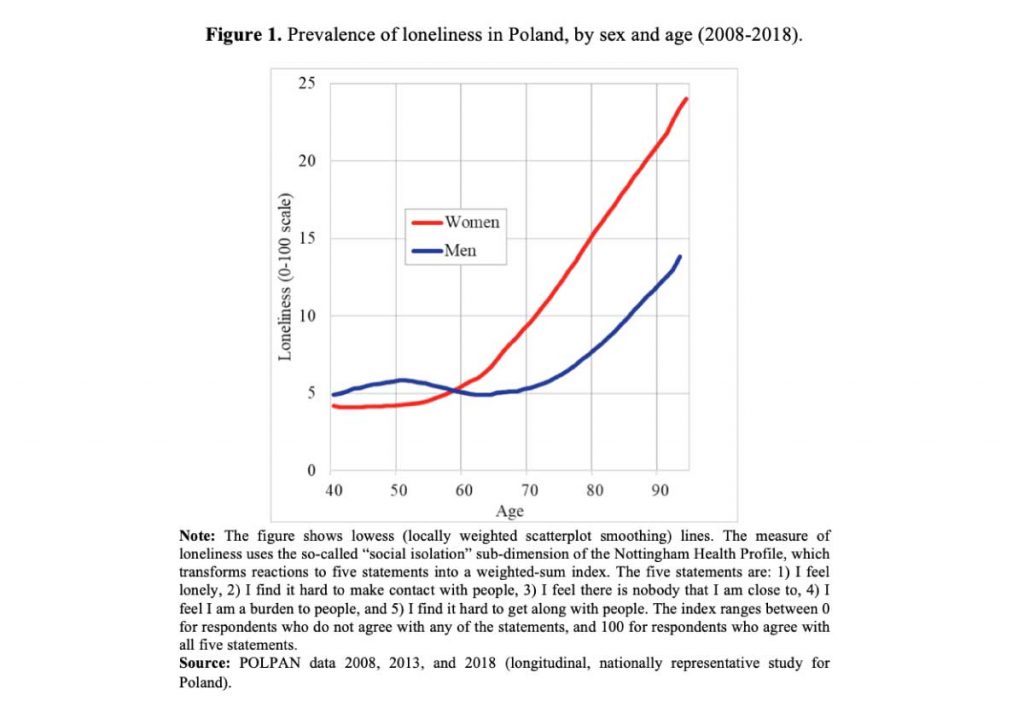

The results show that, in Poland, loneliness increases with age (see Figure 1), starting around age 60 for women, and age 70 for men. Although this is much later than the 30-year starting point found by Yang and Victor (2011), the upward trend begins shortly after retirement, at a much younger age than in Northern and Western Europe.

Triggers of loneliness

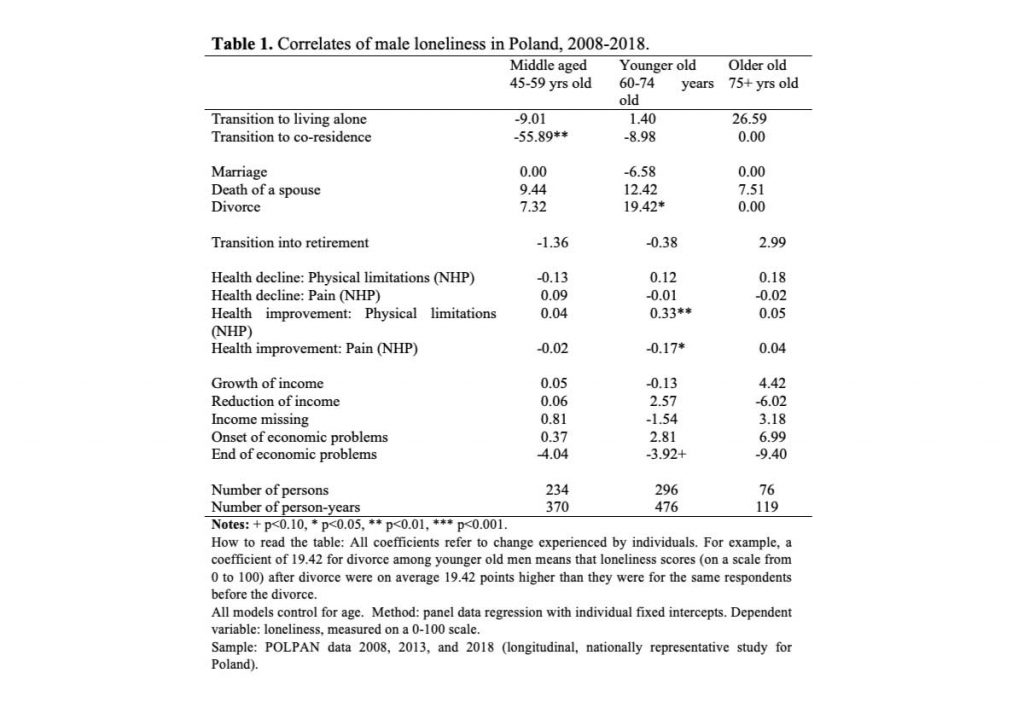

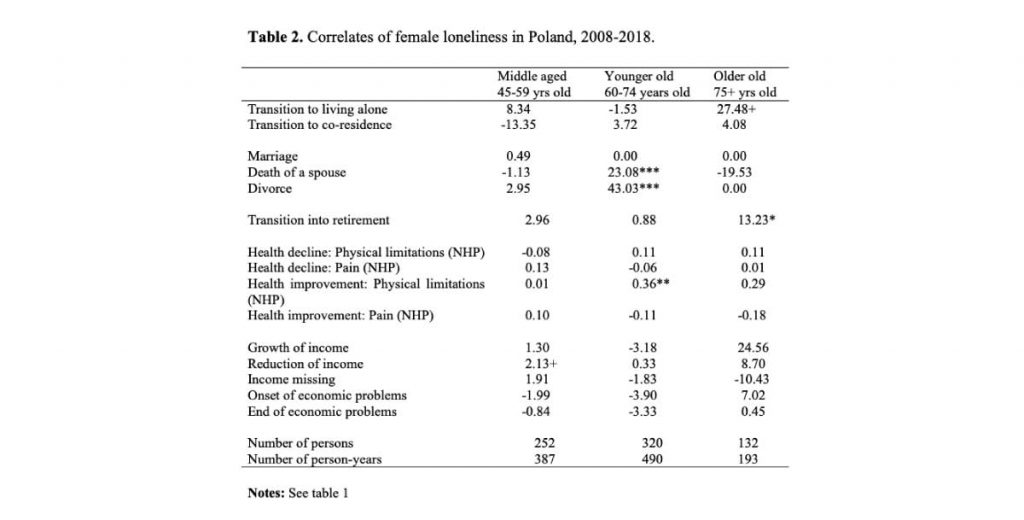

An interesting question is what transitions and events (if any) affect loneliness. Triggers could include changes in social networks and co-residence, changes in the economic situation, transition to retirement, and deterioration or improvement of health. The results of my analysis, summarized in Tables 1 and 2 for men and women, respectively, show that during younger old age, divorce and widowhood are the most powerful triggers of loneliness. Among older old women (aged 75 years and over), transition to retirement and, less consistently, the transition to living alone triggers loneliness. Other factors, such as health decline, worsening of economic conditions, or shrinking networks of friends, did not have this effect.

In principle, certain transitions, such as getting married or moving to live with others, health improvement, or an increase in number of friends, might be expected to alleviate old age loneliness. However, these patterns are rather weak. Among younger old men, only health improvement (reduction in pain) and end of economic problems has an effect. The analysis for woman and for the older old identified no such factors. This discrepancy between results for triggers and inhibitors of loneliness suggests that beyond a certain age, once loneliness sets in it tends to become a chronic state.

Socio-economic disadvantage and loneliness

In another part of my analysis, not reported here, I focused on the influence of current or past social, demographic and economic factors on current loneliness. It turns out that some characteristics of the family of origin (several siblings and unknown father’s education) predict old-age loneliness among men. Besides, low education and economic difficulties in adulthood and in old age are significant predictors of loneliness among men and women. This suggests that old-age loneliness reflects socio-economic disadvantage accumulated over the lifetime and that even early life experiences may cast a long shadow on people’s lives by increasing loneliness as they advance in age.

Conclusions

Loneliness increases most markedly in response to marital dissolution, especially during younger old age, and among women. Other measures of social contacts, such as the changing number of friends, prove much less relevant. The considerable importance of partnership and family relationships is consistent with previous findings on the key role of intimate relationships, especially during old age (Luhmann and Hawkley, 2016). This result may also reflect the specificity of Poland, where family rather than social networks play a particularly prominent role (Fokkema et al., 2012). This may be a legacy of the communist regime which considered social ties as undesirable alternatives to the totalitarian state. Civil society institutions, such as associations and clubs, are still rare, and social trust in the region remains low. All this hampers the creation of ties that could act as alternatives for family- and work-based connections.

References

Błędowski, P., Mossakowska, M., Chudek, J., Grodzicki, T., Milewicz, A., Szybalska, A., Wieczorowska-Tobis, K., Wiecek, A., Bartoszek, A., Dabrowski, A., et al. (2011). Medical, psychological and socioeconomic aspects of aging in Poland: assumptions and objectives of the PolSenior project. Experimental Gerontology, 46(12):1003-1009.

Fokkema, T., De Jong Gierveld, J., and Dykstra, P. A. (2012). Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. The Journal of Psychology, 146(1-2):201-228.

Hansen, T. and Slagsvold, B. (2016). Late-life loneliness in 11 European countries: Results from the generations and gender survey. Social Indicators Research, 129(1):445-464.

Luhmann, M. and Hawkley, L. C. (2016). Age differences in loneliness from late adolescence to oldest old age. Developmental Psychology, 52(6):943.

Mikucka, M. (2021). Loneliness of elderly people in Poland. What triggers it and what are the social differences? In: Slomczynski K. M., I. Tomescu-Dubrow, J. K. Dubrow (Eds), Poland: Thirty Years of Radical Social Change. Brill (forthcoming).

Vozikaki, M., Papadaki, A., Linardakis, M., and Philalithis, A. (2018). Loneliness among older European adults: Results from the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe. Journal of Public Health, 26(6):613-624.

Yang, K. and Victor, C. (2011). Age and loneliness in 25 European nations. Ageing and Society, 31(8):1368.