Healthy grandparenthood: how long is it, and how has it changed?

In North America, grandparents live for longer now than in the past, and spend more years in good health, despite being older. However, Rachel Margolis and Laura Wright also find that less educated, Hispanic, and Black Americans spend less time as healthy grandparents and more time as unhealthy grandparents than well-educated or white Americans.

Being a grandparent can be very fulfilling, and grandparents often play very important roles in their families by providing practical help and having close relationships with their adult children and grandchildren. However, their health affects the role they can play in their families, how involved they can be with their grandchildren, and how they experience grandparenthood.

Today, people in Canada and the US typically become grandparents later than they did in the past because they tend to have children at older ages, and their children also delay their own childbearing (Leopold & Skopek 2015; Margolis 2016). On the other hand, people are also living longer today than in the past, which may extend the time they spend as a grandparent (Margolis 2016). Although life expectancy has been increasing in Canada and the US, not all of the extra years we live are spent healthy. Delayed grandparenthood and longer lives mean that the grandparent stage of life takes place at older ages, when health may be deteriorating.

How long a person is a healthy grandparent depends on the age at which they had children, and at which their adult children start a family, how long they remain healthy, and how long they live. These three factors vary over time, between countries, and across different social groups. We studied how the average length of healthy grandparenthood changed in Canada between 1985 and 2011 using the General Social Survey and life tables from the Human Mortality Database and Statistics Canada, and in the US between 1992 and 2010 using the National Survey of Families and Households, the Health and Retirement Study, and life tables from the Human Mortality Database. We also examined variation by race/ethnicity and education in the US using life tables and the Health and Retirement Study. We used self-reported measures of health to examine the average number of years after age 50 that people can expect to spend in four possible states of grandparenthood and health: healthy grandparent, healthy and not a grandparent, unhealthy and not a grandparent, and unhealthy grandparent.

Changes in the length of healthy grandparenthood over time in Canada and the US

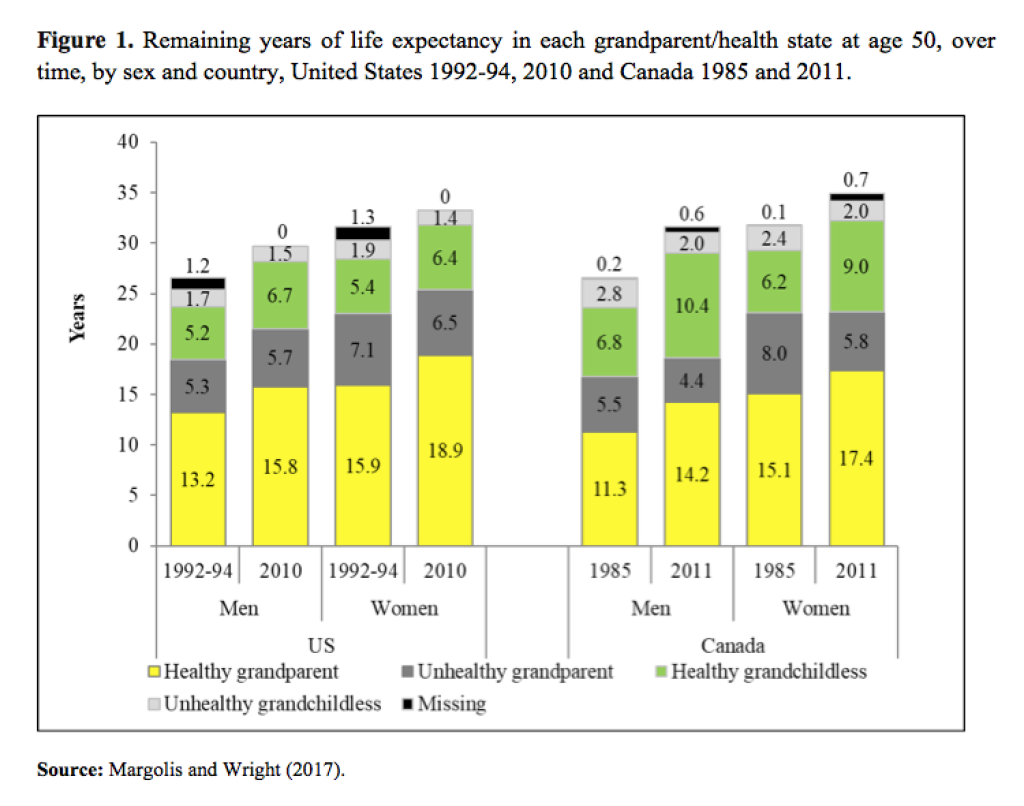

Figure 1 shows the expected number of years at age 50 that Canadian and American men and women spend in each grandparent and health state. We find that people are grandparents for longer on average today than in the past and, more importantly, they are also healthy grandparents for longer; all except American men are unhealthy grandparents for fewer years.

In 1985, Canadian men could expect to be grandfathers for 16.8 years, and healthy for 11.3 of those years, and Canadian women for 23.1 years and 15.1 years, respectively. By 2011, the length of healthy grandparenthood in Canada increased to 14.2 out of 18.6 total grandparent years for men, and 17.4 out of 23.2 total grandparent years for women.

There is a similar pattern of increase in the years spent as a healthy grandparent over time in the US. In 1992, American men could expect to be grandfathers for a total of 18.5 years, and healthy for 13.2 of these years, and women for 23 years, and 15.9 years, respectively. In 2010, the length of healthy grandparenthood increased to 15.8 out of 21.5 total grandparent years for American men, and 18.9 out of 25.4 years for American women.

The number of years spent as an unhealthy grandparent decreased over time for all Canadians, and for American women, but rose slightly for American men between 1992 and 2010, although this increase was more than offset by the extra years spent as a healthy grandfather. In 1992, American men could expect to spend 28.6% of their grandparent years in poor health (5.3 out of 18.5 total grandfather years), versus 25.6% in 2010 (5.7 out of 21.5 years).

Variation in healthy grandparenthood by race/ethnicity and education in the U.S.

Figure 2 shows the average number of years at age 50 that Americans from different racial/ethnic groups, and with different levels of education can expect to have in each grandparent and health state. Hispanic Americans can expect to be grandparents for longer than Black or non-Hispanic white Americans; Black Americans have the shortest expected period of grandparenthood. However, many of the years Hispanic Americans spend as grandparents are also spent with health problems. Hispanic men can expect to be grandparents for 24.6 years, but with only 13.1 years of good health, and Hispanic women for 28.3 years, with 12.8 years of good health. Although White Americans can expect to have a shorter period of grandparenthood than Hispanic Americans, more of these years are spent in good health, with 15 healthy years out of 20.3 years of grandparenthood for men, and 18.5 healthy years out of 24.8 years for women.

There are large differences by education in the average length of healthy grandparenthood. American men with less than 12 years of education can expect to be healthy grandfathers for 11.8 years, versus 16.1 to 16.8 years for men with higher levels of education. Educational differences among women are even greater. American women with less than 12 years of education can expect to be healthy grandmothers for 13.8 years, versus 20.7 or 20.8 years for American women with higher levels of education.

Implications

Grandparenthood is the period when older adults can provide important transfers to their younger kin, such as childcare, if their health allows. Conversely, unhealthy grandparents might require care from the younger generations. We show that, despite the delays in the transition to grandparenthood and the fact that the population of grandparents is now older, the duration of healthy grandparenthood has increased for men and women in both Canada and the U.S over the last two decades, and so has the number of grandparent years spent healthy. Besides, prospects seem to be favorable: as long as life expectancy and health at older ages continue to improve faster than delays in fertility and the transition into grandparenthood, the average time spent as a healthy grandparent will continue to increase, benefitting grandparents and their families. All of this is good news.

However, our study also shows that there is important variation in the time spent as a healthy grandparent by race/ethnicity and education in the US. Less-educated, Hispanic, and Black Americans spend less time as healthy grandparents and more time as unhealthy grandparents than well-educated white Americans.

References

Leopold T., and Skopek J. (2015). The demography of grandparenthood: An international profile. Social Forces, 94, 801–832.

Margolis R. (2016). The changing demography of grandparenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 610–622.

Margolis R. and Wright L. (2017). Healthy Grandparenthood: How Long Is It, and How Has It Changed?. Demography, 6: 2073–2099.