Analysing consecutive birth cohorts in 21 sub-Saharan African countries over the 20th century, Joerg Baten, Michiel De Haas, Elisabeth Kempter and Felix Meier zu Selhausen find that gender gaps first increased and then declined as education expanded. Gender gaps are smaller in southern Africa, in more accessible areas (on the coast, or with access to railroads) and in districts that had a missionary presence in the early 20th century.

Sub-Saharan African girls today are the most disadvantaged in terms of access to schooling. Twelve out of 17 countries in the world that have not yet reached gender parity in primary education are located in sub-Saharan Africa, as are 15 of the 20 that have not achieved gender parity in lower secondary education (UNICEF 2020). In a recent study, we analyzed this phenomenon with a birth-cohort approach, covering most of the 20th century, connecting the colonial with the post-colonial era (Baten et al, 2021). We analyzed gender gaps in education at three levels:

1) comparing sub-Saharan Africa to other developing regions (using data from Barro and Lee 2015);

2) comparing 21 African countries among themselves; and

3) investigating correlates of gender inequality for six decades across 1,177 African birth regions (using census data on 15.4 million individuals from Minnesota Population Center 2019).

Sub-Saharan Africa compared to other developing regions

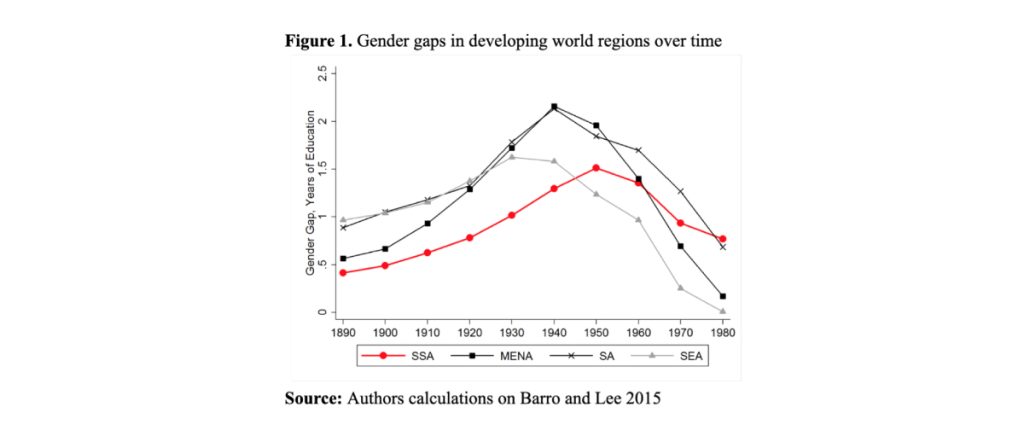

At the beginning of the 20th century, gender gaps, measured in years of schooling, were lower in sub-Saharan Africa than in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA), South Asia (SA) and South East Asia (SEA) (Figure 1). In the early 20th century, a bit later in Sub-Saharan Africa, average educational gender inequality increased everywhere, peaking at between 1.5 and 2.5 years of schooling. By the 1980s, Africa had the highest gender disparities, despite significant post-colonial closure of the gender gap.

The Educational Gender Kuznets Curve

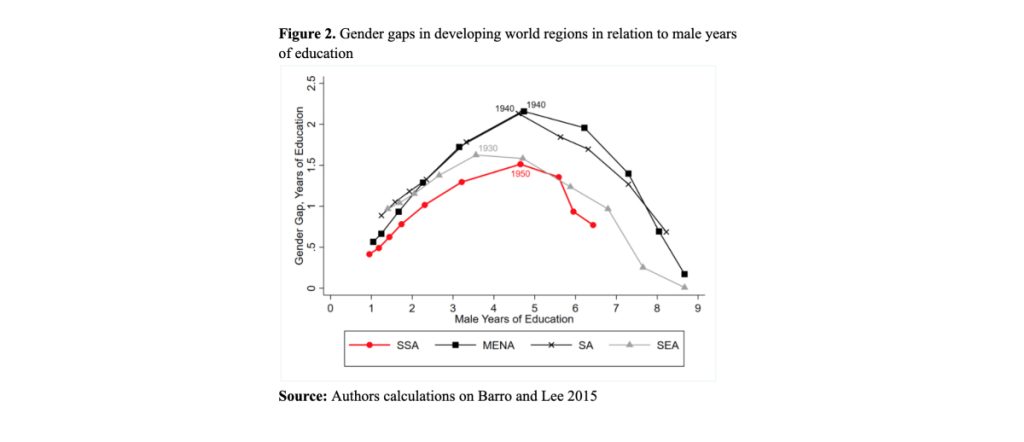

Absolute educational gender gaps provide insight into the unequal accumulation of human capital between boys and girls, but they are more meaningfully interpreted in relation to overall educational expansion. In Figure 2, we therefore express the gender gap in relation to the number of years of education received by boys. Across world regions, this exercise reveals a consistent inverted-U trajectory, which we refer to as the “educational gender Kuznets curveˮ. In this perspective, Africa’s performance in terms of gender equality in education no longer comes out as particularly poor. Consistently across world regions, gender disparities first increased as male education expanded, and then declined after male years of education reached 4-5 years. This is also true for sub-Saharan Africa. In fact, throughout its educational gender Kuznets curve, sub-Saharan Africa performed comparatively well. Educational gender inequality in Africa today is still high, not because of an exceptional tendency to favour boys, but because educational progress is slow in general, and it is still in its early phases.

Results of our African cross-country comparison confirm this pattern of inverted U-shaped educational gender gap trajectories. Almost all of the observed countries saw an initial increase of their gender disparities until the mid-20th century followed by a levelling off or decline. However, countries in southern Africa (South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and, to a lesser extent, Zimbabwe) had remarkably low or even reversed gender gaps throughout the 20th century. This is a striking similarity, since the educational systems of these countries and the degree of overall educational expansion differed markedly between them, despite their geographical proximity. Male absenteeism due to cattle herding and male labour migration for mining activities are likely candidates to explain this more gender-equal southern African pattern, as women were left behind and girls may have taken advantage of their relative immobility to attend (missionary) school.

Understanding sub-national gender gaps in sub-Saharan Africa

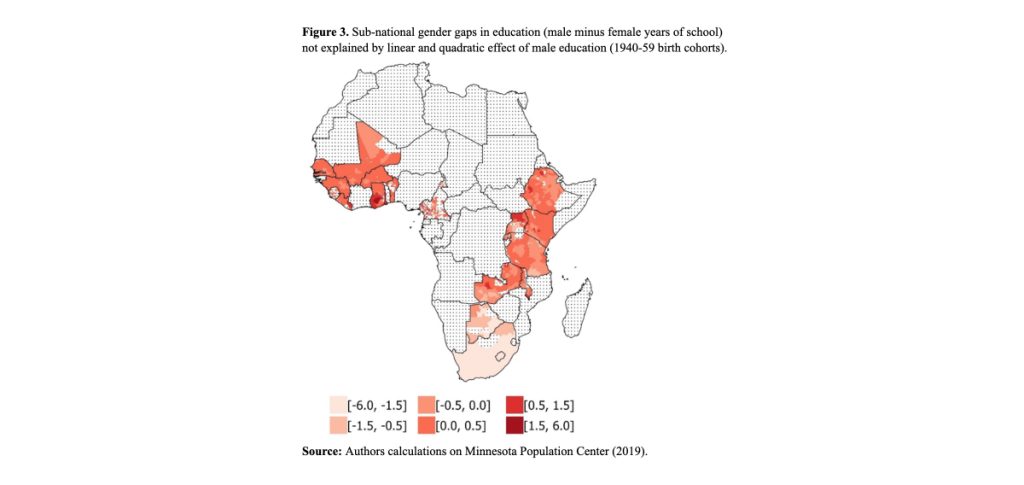

Our world region and country-level analysis builds on an existing literature comparing educational gender gap trajectories at the country-level (see, especially, Barro and Lee 2015). Much less explored is the variation of educational gender gaps within countries, even though these may be expected to be large. To explore sub-national variation, we dig one layer deeper, exploiting the detail provided by IPUMS-curated census data to analyse gender gaps at a fine-grained sub-national region level (Figure 3). Since administrative boundaries change between censuses, we could not consistently trace the educational gender Kuznets curve over time. Instead, we created short birth-cohort panels. We respectively used two decades jointly to analyse three periods (1920-39, 1940-59, 1960-1979) in a multivariate regression framework applying the Least Squares Dummy Variable (LSDV) estimator.

To account for the expected presence of an inversely U-shaped relationship between the gender gap and male educational expansion, we controlled for the linear and quadratic effects of male educational expansion, which again displayed an inverted U-shaped pattern. After controlling for the educational gender Kuznets curve, we were still left with substantial residual regional variation to explain (see Figure 3 for the 1940-59 birth cohorts).

In depth-analysis showed that better connected areas on the coast, with early access to railroads, and those harbouring urban locations achieved greater gender equality in schooling than more remote locations. This supports the idea that increased openness benefited African girls’ education throughout the 20th century. We also found that in districts which formed the heartland of missionary presence in the early 20th century (both Catholic and Protestant), gender gaps were lower throughout the entire period that we studied, even long after mission schools lost their monopoly in British Africa in the late colonial period (Frankema 2012). Conversely, we did not find consistent correlations between educational gender gaps and cash crops, agricultural systems, Islam or family systems.

Closing the educational gender gap?

Addressing Africa’s educational gender gaps today is contingent on a good understanding of their drivers, which in turn requires a long-run perspective. Indeed, educational gender gaps were highly dynamic over the 20th century, increasing rapidly in the early phases of educational expansion, before stagnating or declining in later phases. The bright prospect then is that, as overall education expands further, girls are likely to benefit disproportionally, even without specific policies targeting gender discrimination.

At the same time, we show that countries and regions move through their educational gender Kuznets curves in different ways, some experiencing much larger gaps and slower convergence than others. Our sub-national analysis suggests that closer integration of marginalized regions in national and regional economies will plausibly contribute to more gender equality in educational attainment. Moreover, the persistent correlation between early colonial missionary presence and education gender gaps illustrates how strong and lasting specific local investments in education can be, while also testifying to their limited diffusive effects beyond specific locations.

References

Barro, Robert J., and Lee, Jong-Wha (2015). Education Matters: Global Schooling Gains from the 19th to the 21st Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Baten, Joerg, De Haas, Michiel, Kempter, Elisabeth, and Meier zu Selhausen, Felix (2021). Educational Gender Inequality in Sub‐Saharan Africa: A Long‐Term Perspective. Population and Development Review, 47(3), 813-849.

Frankema, Ewout (2012). “The origins of formal education in sub-Saharan Africa: was British rule more benign?” European Review of Economic History, 16(4), 335-355.

Minnesota Population Center. 2019. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, International: Version 7.2. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS.

UNICEF (2020). Gender and education. UNICEF Data (accessed 20 May 2020) https://data.unicef.org/topic/gender/gender-disparities-in-education/