There is a positive association between tertiary education and internal migration across Europe. Miguel González-Leonardo, Aude Bernard, Joan García-Román and Antonio López-Gay find that this holds also for immigrants: they are more mobile than the native-born (which was known), and especially so those among those who are better educated. This facet of the phenomenon had never been highlighted before.

Educational selectivity of migrants

The association between education and migration is generally positive both between (Docquier and Rapoport 2012) and within countries (Machin et al. 2012), although in the latter case with heterogeneity and exceptions (Bernard and Bell 2018; Ginsburg et al. 2016).

Cross-national variations in the degree of selectivity of internal migration may also be due to differences between population groups. For instance, foreign-born individuals have higher internal migration intensities than the native-born (Catney and Finney 2012). While international migrants are typically positively selected in terms of education compared to the population at origin (Docquier and Rapoport 2012), less is known about the role of education in shaping their internal migration once in destination countries. Answering this question is particularly important in Europe where the share of foreign-born population has been trending up, coupled with the fact that internal migration plays an important role in mitigating regional population ageing (Lee 2011) and in improving the functioning of the labour market, by bringing workers and skills where they are needed (Van Ham et al. 2001).

In a recent paper (González-Leonardo et al 2022), we used data from the European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS) of 2015‒19 to establish the educational selectivity of internal migrants between NUTS-2 regions, distinguishing between native and foreign-born-individuals in 12 European countries: Germany, United Kingdom, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovenia.

Tertiary education increases internal migration, especially among foreigners

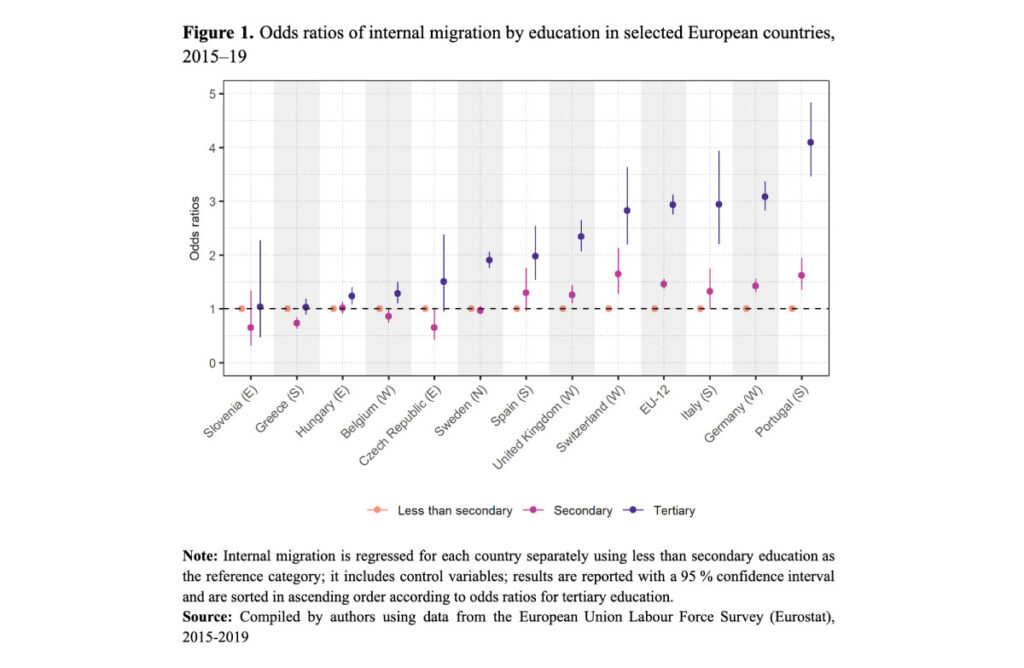

Tertiary education, compared to low education (less than secondary), tends to increase the likelihood of migrating internally by about a factor of three (Figure 1). This is true in all the European countries under observation except for Slovenia, Greece and the Czech Republic. In some cases the relative increase is very strong: up to a factor or four in Portugal, and about three in Germany, Italy and Switzerland.

Secondary education, conversely, has a lower impact, of the order of 1.46 (i.e., people who have completed secondary education are 46% more likely to migrate internally than those who have not), but the association is not always significant, and not everywhere with the expected sign.

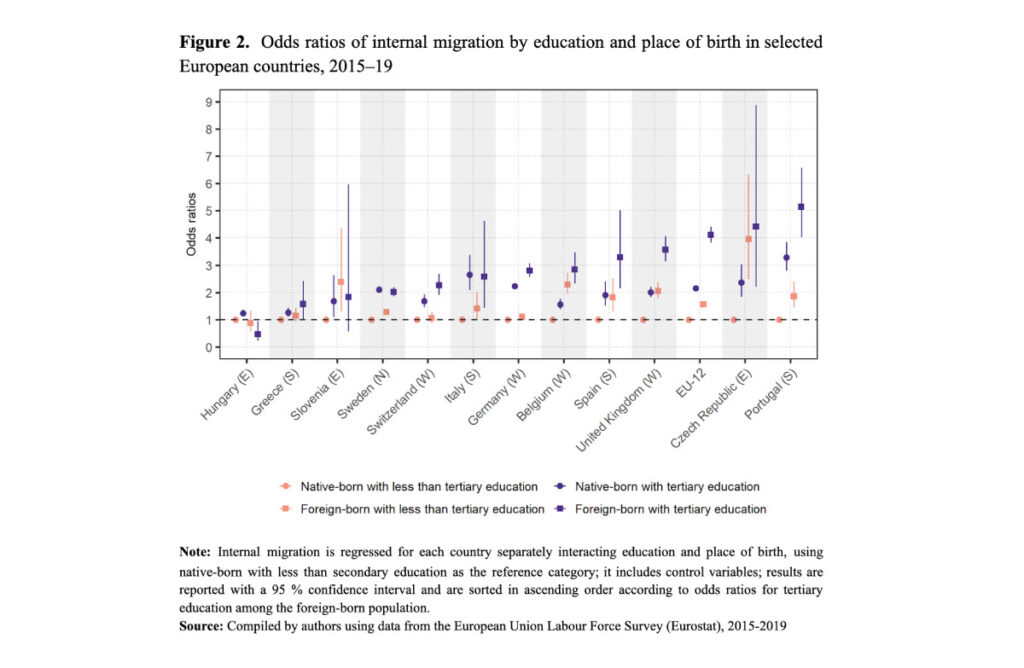

Figure 2 shows that foreign-born populations are generally more likely to move than the native-born at all educational levels, and they are positively selected. The foreign-born with less than tertiary education are 1.72 times more likely to migrate than the native-born with a comparable level of education, while the foreign-born with tertiary education are 4.1 times more likely to migrate than the tertiary-educated native-born.

As a result, tertiary-educated immigrants are the most mobile group in all countries, except in Greece and Slovenia, where there is no association, and in Hungary, which displays a negative selection for tertiary-educated immigrants but a marginally positive selection for the native-born. Only in Sweden and Italy is the probability of internal migration similar for both the foreign-born with tertiary education and their native-born counterparts.

Immigrants play a key role in redistributing skills within the European countries

In short, tertiary education has a strong effect on the likelihood of migrating internally, while the impact of secondary education is generally positive but much lower, and with several exceptions. This combines with the higher propensity to migrate among the foreign-born: tertiary-educated immigrants are the most mobile group in almost all countries (excluding Hungary, Sweden and Italy). This is an important finding that complements the literature on educational selectivity on international migrants (Docquier and Rapoport 2012) by showing that the foreign-born internal migrants are also positively selected by education in destination countries.

To be sure, there are cross-national differences, which suggest that the effect of education on immigrant’s internal migration may be shaped by contextual factors, such as the socio-economic profile of immigrants in each country, national labour market dynamics and the interaction between these two elements, which ultimately reflects the degree of immigrants’ integration in local economies.

References

Bernard, A., and Bell, M. (2018). Educational selectivity of internal migrants. Demographic Research, 39(29): 835-854. https://doi.org/10.4054/demres.2018.39.29.

Catney, G. and Finney, N. (2012). Minority internal migration in Europe. London: Routledge. https://doi.org//10.4324/9781315595528.

Docquier, F., and Rapoport, H. (2012). Globalization, Brain Drain, and Development. Journal of Economic Literature, 50(3): 681-730. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.50.3.681.

Ginsburg, C., Bocquier, P., Béguy, D., Afolabi, S., Augusto, O., Derra, K., Odhiambo, F., Otiende, M., Soura, A., and Zabré, P. (2016). Human capital on the move: Education as a determinant of internal migration in selected INDEPTH surveillance populations in Africa. Demographic Research, 34(30): 845-884. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2016.34.30.

González-Leonardo, M., Bernard, A., García-Román, J., & López-Gay, A. (2022). Educational selectivity of native and foreign-born internal migrants in Europe. Demographic Research, 47(34), 1033-1046. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2022.47.34.

Lee, R. (2011) The outlook for population growth. Science, 333(6042): 569-573. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1208859.

Machin, S., Salvanes, K.G., and Pelkonen, P. (2012). Education and mobility. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10(2): 417–450. https://doi.org//10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01048.x

Van Ham, M., Mulder, C.H., and Hooimeijer, P. (2001). Spatial flexibility in job mobility: Macrolevel opportunities and microlevel restrictions. Environment and Planning A, Economy and Space, 33(5): 921–940. https://doi.org//10.1068/a33164.