Endogamy (partners of the same geographical origin) is said to lower the risk of marriage dissolution. However, once cohabitation is included in the analysis of Belgian (register) data, Layla Van den Berg and Dimitri Mortelmans say, differences in dissolution risks between exogamous and endogamous couples become smaller or disappear entirely.

Better to stick with your own kind?

What we know from the literature on couple formation and dissolution is that people are more likely to choose a partner who belongs to the same origin group (Kalmijn, 1998) and that, upon marriage, these endogamous couples are also less likely to divorce. Higher divorce risks for exogamous couples are generally explained by differing preferences, values, norms and communication styles that make it harder to take joint decisions, such as spending free time, buying a home, and raising children. In addition, family and the broader community may sanction people who choose a partner outside their (origin) group, for instance by withholding support. Exogamous couples are also more likely to face discrimination and public disapproval, which may affect the quality of their life, undermining the stability of their relationship.

However, the literature that links endogamy to lower divorce risks has focused almost solely on married couples, ignoring unmarried cohabitation. This is scarcely justifiable in contexts such as the European one, where unmarried cohabitation has risen both as a living arrangement that precedes marriage and as an alternative to it (Billari & Liefbroer, 2010). In addition, both the prevalence and the perception of unmarried cohabitation can differ strongly between majority and minority groups. In the case of Belgium, for instance, unmarried cohabitation is widely accepted among natives, but it is often regarded as unstable and unreliable among couples with a Turkish or Moroccan background.

Couple dissolution, with and without unmarried cohabitation

With regard to Belgium, we investigated the matter in a recent publication. Using data from the Belgian Social Security Register between 1998 and 2013, we analyzed the four largest immigration communities (from Southern Europe, Morocco, Turkey and Congo/Burundi/Rwanda, respectively), although in what follows, for reasons of space, we will briefly discuss only the Moroccan and the Turkish cases (Van den Berg & Mortelmans, 2022).

We found support to previous studies showing that, among marriages without a period of premarital cohabitation, endogamy goes along with lower divorce risks. However, we also found that couples that have been involved in unmarried cohabitation show substantially different patterns. Among the couples who married after premarital cohabitation or remained unmarried throughout the observation period, dissolution risks of exogamous couples barely differ from endogamous Southern European, Turkish, and Moroccan couples (the three most relevant immigrant communities in Belgium), and may even prove more resilient.

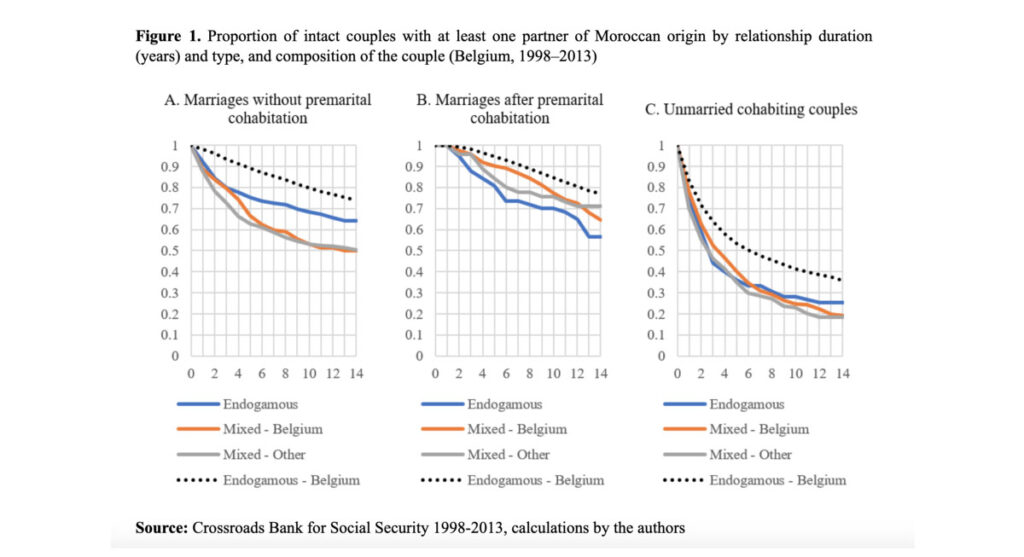

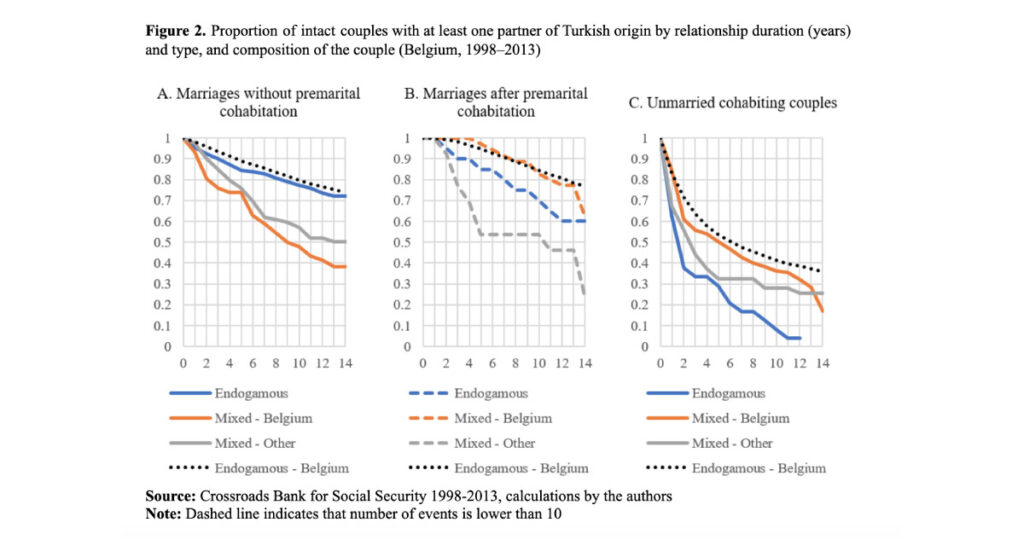

While more can be found in our original article, illustrative evidence for the couples with at least one partner of Moroccan or Turkish origin can be found in Figure 1 and Figure 2, respectively. All types of couples are less resilient than endogamous Belgian ones, but the “advantage” of endogamy emerges only in the case of direct marriage.

Conclusion

In short, unmarried cohabitation matters and it should not be disregarded when studying the dissolution of endogamous and exogamous relationships. Although the literature states that crossing group boundaries generally results in higher divorce rates compared to forming a relationship within one’s own origin group, this does not always appear to be the case for marriages formed after a period of unmarried cohabitation, or at least not in Belgium in the period under study (1998‒2013).

This may be in part the result of selection: cohabitation may be a sort of “trial marriage” where partners test their compatibility, the absence of which precludes marriage, later on. However, panels C of Figures 1 and 2 suggest that also among cohabiting couples who do not “evolve” into a marriage, all of whom are comparatively more fragile than others, endogamy is not a protecting factor.

As exogamous couples cross an important symbolic boundary, they are likely to be tested more severely. Compared to their endogamous equivalent, they may experience a stronger social burden and may benefit from less social and family support. Unmarried cohabitation may therefore offer a less visible alternative to marriage for mixed couples, who can experiment with their relationship while minimizing the pressure and possible social sanctions from family and the broader community. This can provide an opportunity to navigate more easily the specific challenges associated with exogamy.

References

Billari, F. C., & Liefbroer, A. C. (2010). Towards a new pattern of transition to adulthood? Advances in Life Course Research, 15(2-3), 59‒75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcr.2010.10.003

Kalmijn, M. (1998). Intermarriage and homogamy: Causes, patterns, trends. Annual review of sociology, 395-421. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.395

Van den Berg, L., & Mortelmans, D. (2022). Endogamy and relationship dissolution: Does unmarried cohabitation matter? Demographic Research, 47, 489‒528. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2022.47.17