Status exchange is a leading factor behind the rising share of educational hypogamy marriages in India (women marrying less educated men), says Koyel Sarkar. Lower caste women aspire to upward mobility by caste, while higher caste women look for husbands with good employment status. Men with these desirable characteristics may “qualify for the job”, even if their educational level is low.

Background

As the gender educational gap shrinks, homogamy, i.e. a woman marrying an equally educated husband, eventually takes over hypergamy (a woman marrying a higher educated husband) (Kalmijn and Flap 2001). Hypogamy (marrying a less educated husband), on the other hand, is a distinguishing feature of western societies, where the gender gaps have reversed and women have become more educated than men (Van Bavel 2012).

In India, female education has increased at a faster rate than men’s over recent decades: according to DHS estimates (2019–21), “no education” among women decreased from more than 54% in 1971 to less than 12% in 2003, and in the same period “secondary education” increased from 26% to 76%. However, women are still less educated than men: literacy rates, for instance, were 71.5% for females and 84.3% for males in the 2019–21 DHS Indian survey.

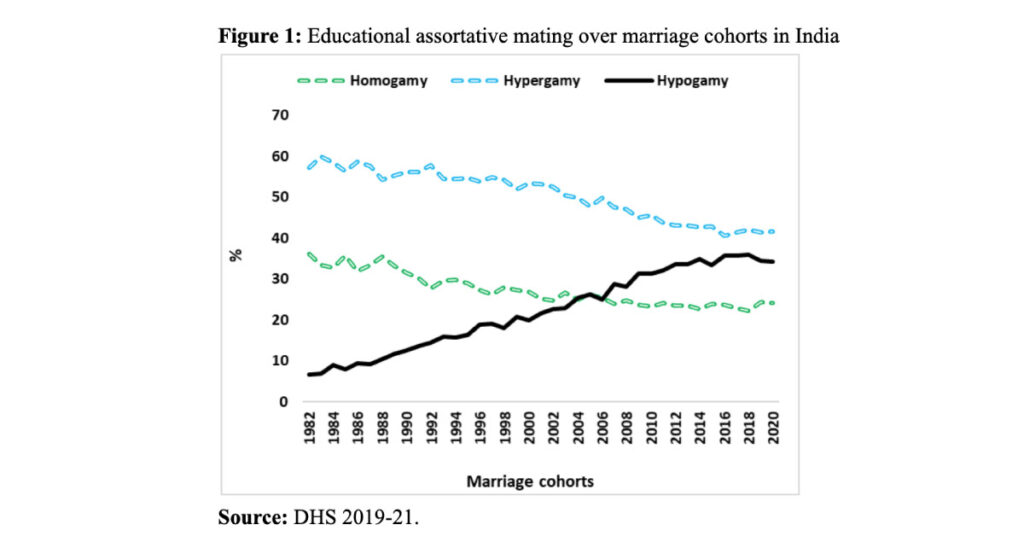

It is therefore surprising to observe that hypogamy has increased from 5% to 35% over four decades of marriage cohorts (Figure 1). How can this be explained?

Theoretical background

Relatively little is known about couple formation in India, and the question arises as to whether the “status-exchange” theory applies. According to this theory, individuals lacking a characteristic that they consider desirable tend to marry partners with precisely that characteristic – and as this quest for “improvement through marriage” applies to both genders, status exchange takes place, each partner bringing to the couple something that the other partner lacks and deems valuable (Davis 1941). In India, increasing educational hypogamy, particularly among the lower caste groups, and an overall rise in caste exogamy (Ahuja 2016; Sarkar and Rizzi 2020; Sarkar 2022) suggest that status exchange mechanisms could be the potential driver.

Caste, education and occupation

Caste is a unique, very ancient feature of the Indian society. Although formally abolished in 1947, in practice it continues to operate, especially in rural settings and for certain social practices, such as marriage. The system is very complex, with thousands of castes and sub-castes, characterized by endogamy and social hierarchy (Ahuja 2016).

For our purposes, let us just focus on four large groups:

1) general castes, i.e. all those not listed below. These are relatively affluent and at the top of this reduced hierarchy

2) the less privileged caste groups, which can be broken down into three categories, in decreasing hierarchical order:

2.a) other backward classes (OBC),

2.b) scheduled castes (SC), and

2.c) scheduled tribes (ST).

Female education in India seems to play a peculiar role. It is not of great help to women in the labour market, where their participation is limited and irregular, even when they do have some education (Chatterjee 2018). Instead, in the marriage market, educated women are preferred because of their greater abilities in caring for children and managing household health. Thus, trading higher educational status for upward caste mobility seems to be a profitable strategy, especially for women from lower castes. Women who belong to higher caste groups, on the other hand, have little incentive to marry a higher caste husband: in their case, a better-employed or a financially secure husband may be more attractive.

For men, given that the caste system is traditionally patrilineal, a highly educated wife is desirable, irrespective of her caste

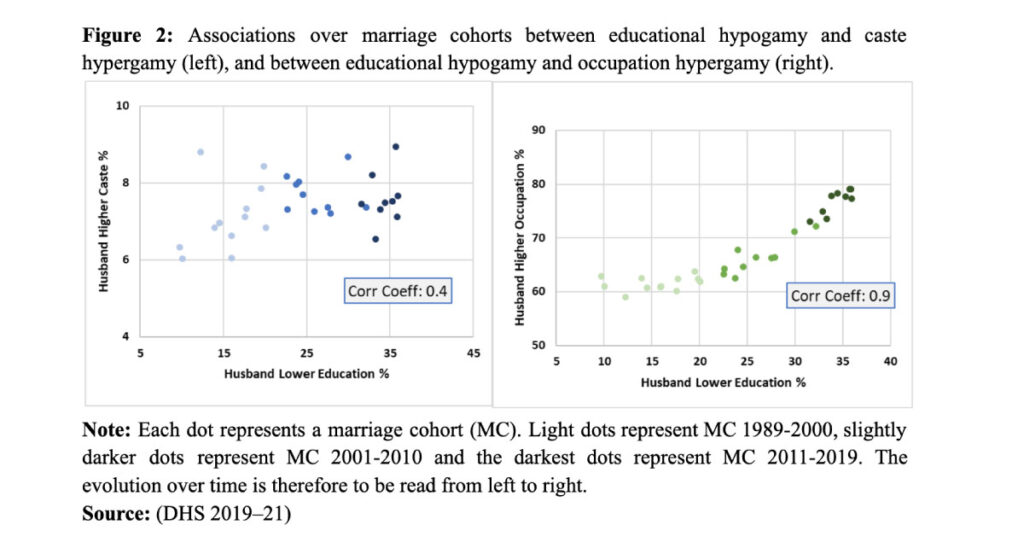

Empirical data indeed show a positive correlation across marriage cohorts: greater proportions of women marrying low-educated husbands coincides with husbands belonging to higher castes, (Figure 2, left panel) and holding more prestigious (and better paid) jobs (Figure 2, right panel).

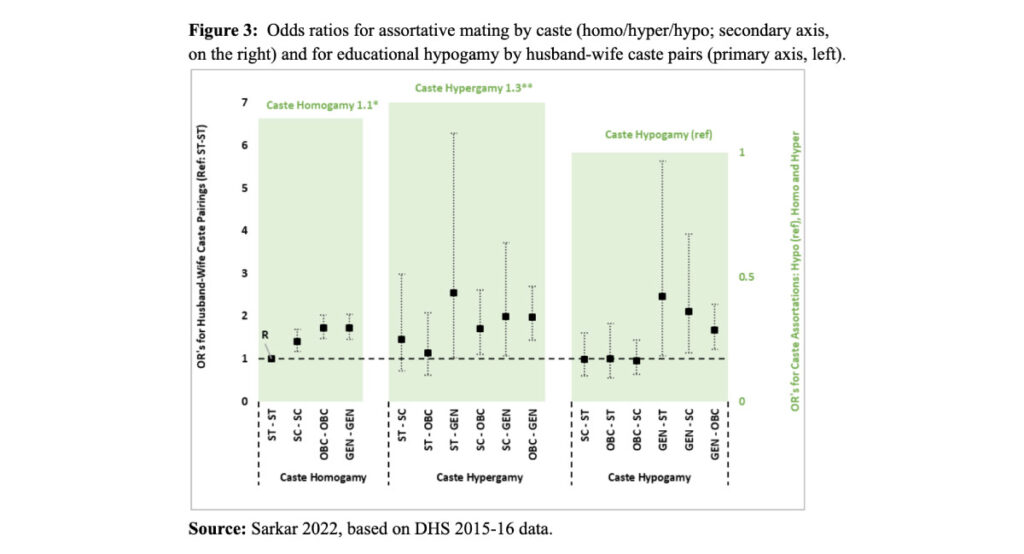

The general preference for all education-caste-occupation subgroups is to marry within the same caste. However, the odds of marrying a higher-caste husband are highest for educational hypogamy (Figure 3; ORs: 1.3**, secondary axis). Additionally, when all husband-wife caste pairs are considered for each caste-wise assorted group, the highest odds are for caste hypergamous pairs: among the ST (ORs: 2.5**), SC (ORs: 2.0**), and OBC (ORs: 2.0***), women “marrying up” to general caste husbands. In addition, higher caste women who “marry down” both by education and caste are actually “marrying up” by occupation, when the pairs are further decomposed by partner’s occupation (Sarkar 2022).

Conclusions

Socio-economic status exchange by caste, education, and occupation seems to be at work in the Indian marriage market, and it may explain the increase in educational hypogamy. Education-caste exchange applies to lower caste women while education-occupation exchange applies to higher caste women. As such, the social and/or economic incentives are specific to the caste rank to which the women belong.

Status exchanges in Indian marriages are blurring the traditionally rigid caste boundaries, thanks to women’s higher educational achievements. Unfortunately, however, the factors behind these exchanges run counter to the expectation that education leads to empowerment. Despite often being better educated than their partners, Indian women seek economic advantages through their prospective husbands rather than engaging in the labor market themselves. This is a consequence of the conservative norms that discourage Indian women from working. Secondly, the desire for upward social mobility by caste shows that social inequalities are not necessarily diminishing, and that they still play an important part in the workings of the marriage market.

References

Ahuja, A. and Ostermann, S.L. (2016). Crossing caste boundaries in the modern Indian marriage market. Studies in Comparative International Development. 51(3): 365–387. Doi:10.1007/s12116-015-9178-2.

Chatterjee, E., Desai, S., and Vanneman, R. (2018). Indian paradox: Rising education, declining women’s employment. Demographic Research 38(31): 855–871.doi:10.4054/DemRes.2018.38.31.

Davis, K. (1941). Intermarriage in caste societies. American Anthropologist 43(3): 376–395. Doi:10.1525/aa.1941.43.3.02a00030.

Kalmijn, M. and Flap, H. (2001). Assortative meeting and mating: Unintended consequences of organized settings for partner choices. Social Forces 79(4): 1289–1312. Doi:10.1353/sof.2001.0044.

Sarkar, K. and Rizzi, E.L. (2020). Love marriage in India. Démographie et sociétés. Louvain la Neuve, Université Catholique de Louvain. (Document de travail 14).

Sarkar, K. (2022). Can status exchanges explain educational hypogamy in India?. Demographic Research, 46(28), 809-848. Doi:10.4054/DemRes.2022.46.28.Van Bavel, J. (2012). The reversal of gender inequality in education, union formation and fertility in Europe. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research 10: 127–154. doi:10.1553/populationyearbook2012s127.