What are the trends in the prevalence of child support agreements in the US? Apparently declining, based on frequently used stock data, but in fact stable or even on the increase, using flow data instead, as Maria Cancian, Molly A. Costanzo, and Daniel R. Meyer do here.

Child support, in which a noncustodial parent (with whom the child does not primarily live) provides financial support towards raising a child, is crucial for the approximately 3.8 million U.S. custodial-parent families, often on low incomes, who have a child support agreement (Grall 2020). Child support’s reach and potential have motivated substantial interest in the child support program, which administers policies governing the establishment and enforcement of child support agreements.

Fewer and fewer agreements

The Child Support Supplement (CSS) of the Current Population Survey (CPS) shows that the proportion of custodial-parent families with such agreements increased slightly from 57% in 1993 to 60% in 2003, but then declined, and has been stable at about 50% since 2009 (Grall 2020). The growing share of custodial fathers, who are less likely to have agreements than custodial mothers, has contributed to this decline, but the share of custodial mothers with agreements has also fallen sharply, from a high of 64% in 2003 to 51% in 2017 (Grall 2020). This downtrend raises questions about whether child support policy has become less effective.

A key limitation of the dominant empirical approach to studying trends in child support is that it examines the stock of all custodial parents. To evaluate policy changes, flow measures, categorizing parents by when they enter the system, are more appropriate than stock measures, because the latter can be distorted by compositional variations and other issues. Indeed, previous demographic work from a variety of policy realms shows notable differences in stock and flow outcomes (e.g., Abramowitz 2016; Bitler et al. 2004; Herbst 2011; Klerman & Haider 2004).

We use CPS-CSS data on child support agreements from 1994 through 2018, differentiating between snapshots of custodial mothers in various survey years (the stock) from our estimates of outcomes for mothers who are new to child support in various years, either because they were recently divorced or had a nonmarital birth (the flow). We are primarily interested in legal agreements (rather than informal agreements) about child support, both those that do and do not impose support payments (a child support order).

Stocks 1993-2018

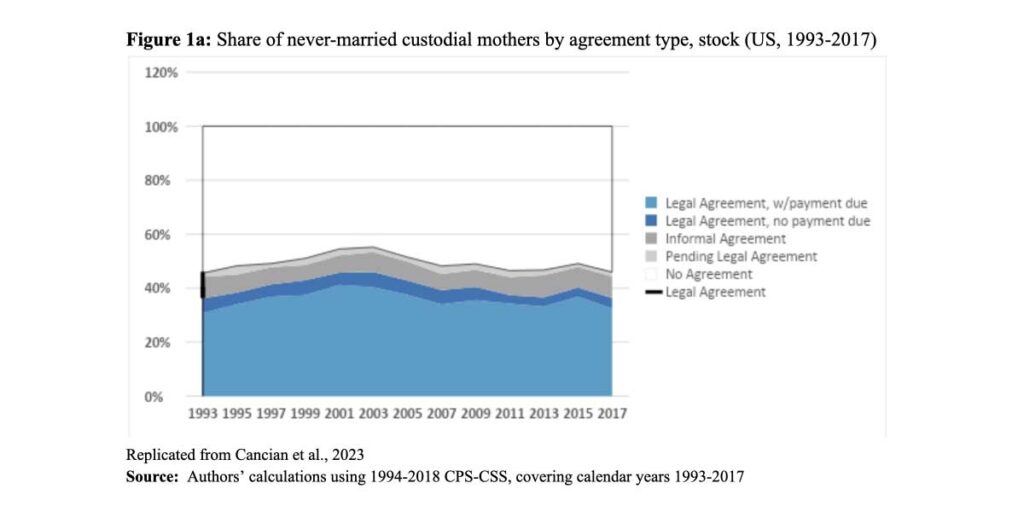

Never-married and ever-married custodial mothers have different outcomes, in part because divorce requires a legal act, so legal child support agreements may be more frequent among ever-married parents. The proportion of never-married custodial mothers with legal agreements peaked in 2003 at around 46% and the proportion having a legal agreement with support order peaked at 41% in 2001 (Figure 1a). Both proportions then declined through 2013, with just one-third of mothers reporting a legal agreement with a support order in that year. Although both proportions increased somewhat in 2015, they again declined in 2017. The proportions of never-married mothers with pending agreements and informal agreements were relatively small and showed no consistent trends.

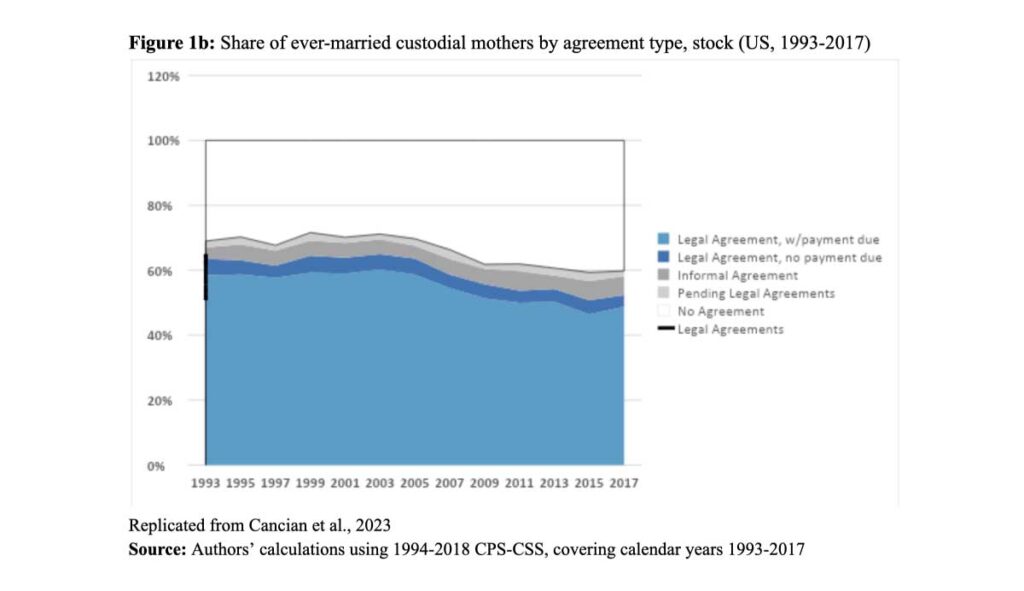

Ever-married custodial mothers more often have agreements than never-married mothers, but their trends have been similar (Figure 1b). After a peak in 2003 (65% with legal agreements, 60% with an amount due), the proportions began to decline steadily, though not substantially after 2011. For ever-married mothers, in 2017 just over half reported a legal agreement, and just under half reported a support order. The proportions with pending legal agreements and informal agreements were both small.

Thus, using the stock of cases, we see the prevailing understanding: the proportion of custodial mothers with legal agreements and the proportion with a child support order increased early in this period but appear to have declined more recently for both never- and ever-married mothers.

Trends 1994-2018

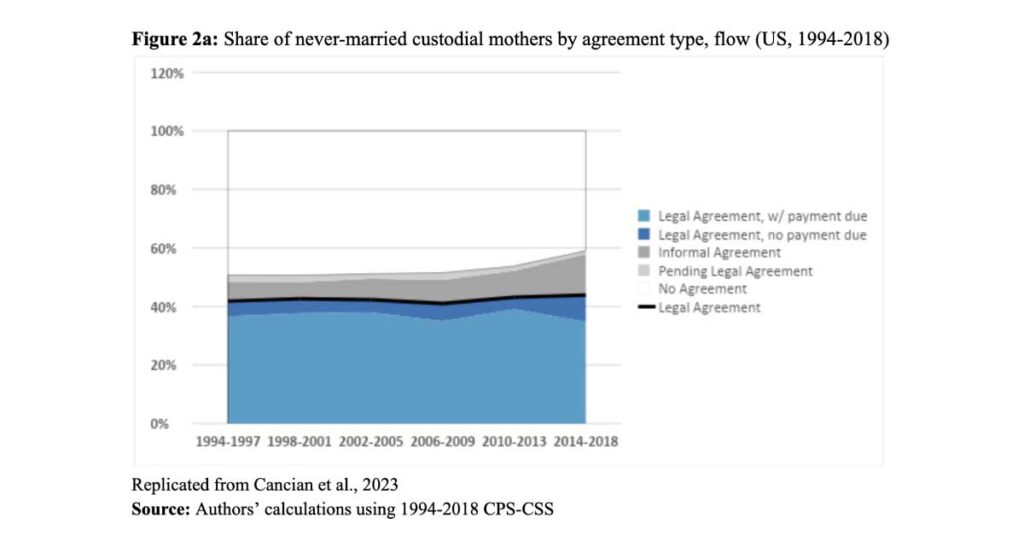

Trends as measured by the flow of child support cases, however, provide a different picture. For never-married mothers (Figure 2a), the proportion with legal agreements was relatively stable, between 41% and 44% over this period. However, the relative stability in the proportion with legal agreements masks more fluctuation in the proportion with a support order, which declined to 35% at the end of the period. Moreover, the proportion with informal agreements rose, from around 6% in the early cohorts to 14% in the most recent cohort. For never-married mothers, then, the simplest outcome measure (the proportion with legal agreements) shows some modest differences: stock measures show a decline since the mid-2000s and flow measures suggest relative stability.

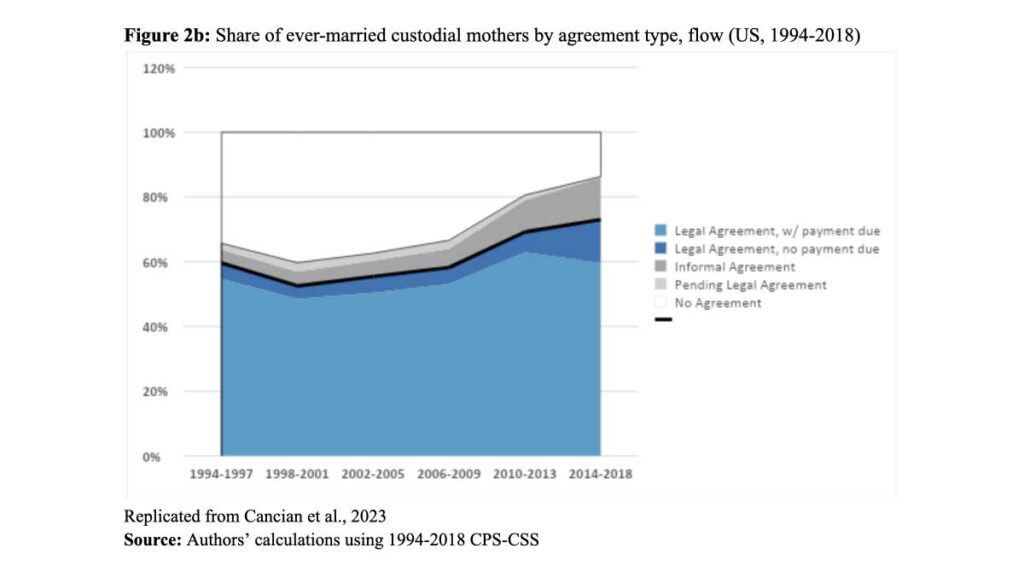

For ever-married mothers, the stock and flow comparisons are quite different. Whereas the stock suggests a slight increase in agreements for ever-married mothers through the mid-2000s followed by a decline, the flow indicates a decline in the prevalence of legal agreements among mothers entering the system in the first years of our analysis followed by a substantial increase for those entering in 2010 and beyond (Figure 2b). Similar to never-married mothers, there is some increase in the proportion with legal agreements without a support order. These increases in legal agreements, combined with an increase in informal agreements in the same period, results in a lower level of recent ever-married mothers with no agreement; beginning in 2010, fewer than 20% of all ever-married mothers have no agreement in place. These simple descriptive trends substantially hold in multivariate analyses that control for race, ethnicity and education.

Conclusions

Our findings reinforce the importance of understanding differences in stock and flow measures and why these may matter for our understanding of a variety of policy-relevant outcomes. To assess policy effectiveness, flow measures are preferable, because they focus on the variable of interest, while stock measures may give a distorted picture due to changes in population demographics.

The prevailing narrative, that child support orders and agreements are becoming less prevalent, is the result of looking only at the stock. Looking at the flow shows that legal agreements for ever-married mothers are actually becoming more prevalent, and that the share is essentially stable (or perhaps even increasing) for never-married mothers. Our analysis also suggests increases in informal agreements and in legal agreements with no support order. Calls to reform the child support program because of presumed declines in agreements are not based on the whole picture.

References

Abramowitz, J. (2016). Saying, “I don’t”: The effect of the affordable care act young adult provision on marriage. Journal of Human Resources, 51(4), 933-960.

Bitler, M. P., Gelbach, J. B., Hoynes, H. W., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41(2), 213-236.

Cancian, M., Costanzo, M. A., & Meyer, D. R. (2023). A research note on trends in the stock and flow of child support agreements. Demography online in advance of print, https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-11075477

Grall, T. S. (2020). Custodial mothers and fathers and their child support: 2017 (P60-279). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau.

Herbst, C. M. (2011). The impact of the Earned Income Tax Credit on marriage and divorce: Evidence from flow data. Population research and Policy review, 30(1), 101-128.

Klerman, J. A., & Haider, S. J. (2004). A stock-flow analysis of the welfare caseload. Journal of Human Resources, 39(4), 865-886.