In a recent study (Väisänen 2017), I examined how women make decisions to terminate a pregnancy within the wider context of their lives – including the state and quality of their romantic relationships.

We know that childbearing decisions are influenced by decisions to continue or leave a romantic relationship (Lillard and Waite 1993; Steele et al. 2005). Much less is known about pregnancy terminations, because typically only around a half of them are reported in surveys (Jones and Kost 2007).

To overcome this limitation, I used administrative data, where data on abortion experiences come from women’s medical records rather than self-reports and thus are not underreported. A shortcoming of administrative data is that it does not provide information on some relevant individual traits, such as attitudes or religious beliefs. However, with the help of appropriate statistical models, the influence of unobserved characteristics on the decision-making processes around abortions and union dissolutions can be quantified and analysed.

The context

In Finland, it has been relatively easy to obtain an abortion since legislation was liberalised in the 1970s. All municipalities have been legally required to provide family planning services since 1972. Many policies that reduce the cost of childbearing have been implemented over time: education is free of charge at all levels, day-care of children is subsidised by the government to enable both parents to work, and parental leave is subsidised at around 70% of the income level prior to childbearing.

Unstable union experiences associated with more abortions

In my analysis, I followed 17,666 women born in 1965-69 from the year they turned 15 until year 2010, when they were in their early 40s. The data included information about the women’s level of education, relationship status, births and abortions in each year. Twenty-three percent of women in the sample had at least one abortion in the course of this study.

Women who experienced a higher number of marriages or cohabiting unions also obtained a higher number of abortions. This could also be due to individual characteristics, which could not be observed in this study, such as religiousness, attitudes, and personality. Religiousness is often associated with negative attitudes towards abortion (Ellison, Echevarría, and Smith 2005; Hess and Rueb 2005) and lower approval of divorce. Thus, religiousness may be associated with a lower likelihood of separating from a partner as well as obtaining an abortion. Personality traits, such as high extraversion, low emotional stability, and low conscientiousness, have been associated with a higher likelihood of experiencing an unintended pregnancy (Berg et al. 2013) – perhaps these traits also correlate with union stability.

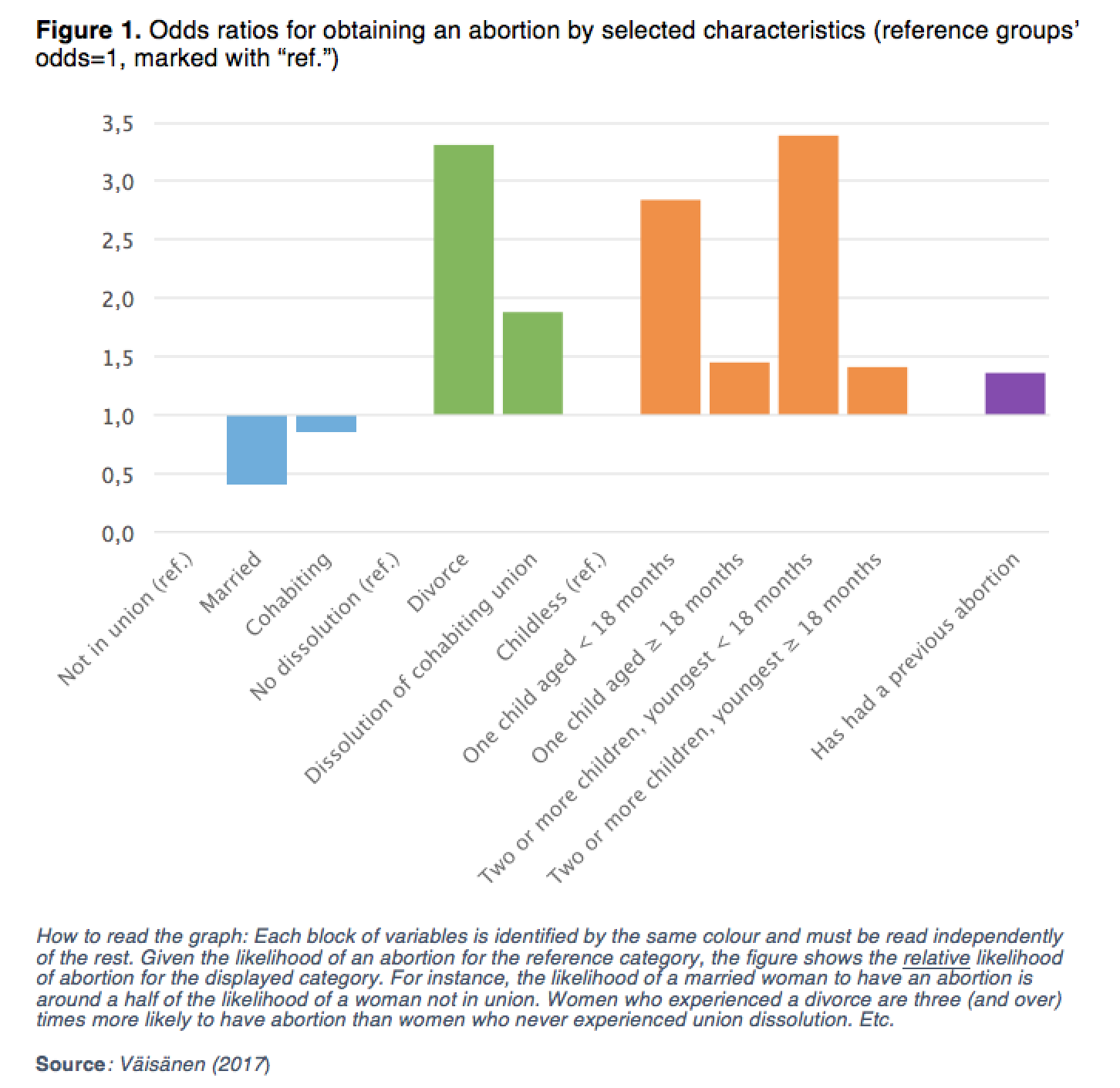

When it comes to characteristics that were observed in these data, interestingly, divorce was associated with a higher likelihood of obtaining an abortion during the same calendar year than separation from a cohabiting partner (Figure 1). Women may be less likely to want children due to the added cost of breaking up if children are involved (Lillard and Waite 1993): they are therefore more likely to terminate a pregnancy than those in a stable relationship.

Previous pregnancies also mattered for abortion decisions: women whose youngest child was 18 months old or younger had a higher likelihood of abortion than women with no children or older children (Figure 1). Those with a previous experience of abortion had a slightly higher likelihood of terminating a pregnancy than those without previous abortion(s), but the effect was relatively small (Figure 1).

Does it matter if you are married or cohabiting?

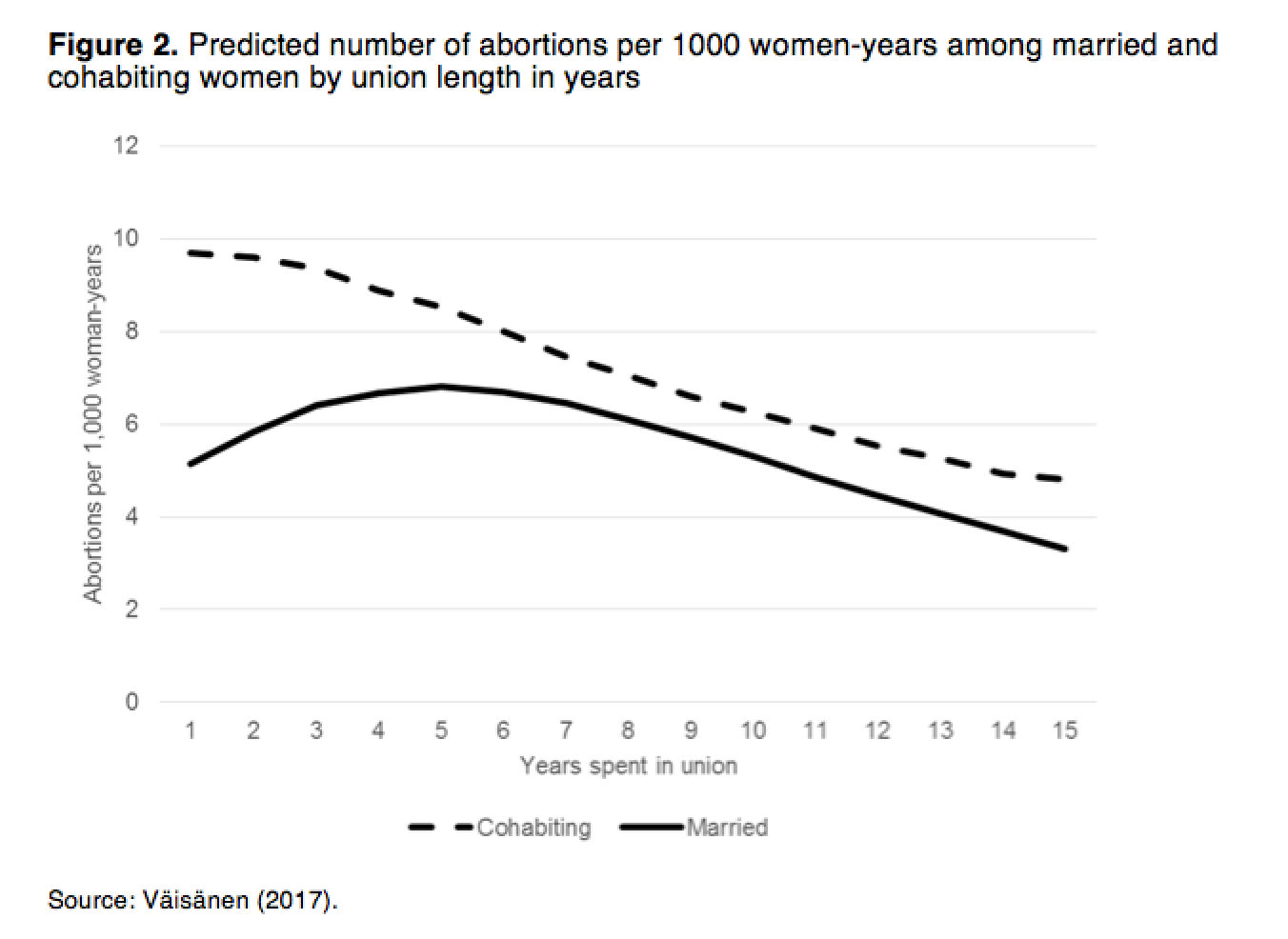

The likelihood of abortion was higher for women who were cohabiting with a partner than for married women during approximately the first five years of the relationship (Figure 2). Perhaps some cohabiting women decided to terminate an unintended pregnancy because they felt that the relationship was not yet ready for childbearing, whereas it may be less likely for married women to feel that way. However, only a very small difference in abortion levels remained after the first five years of co-residence. This is in line with studies showing that cohabiting couples tend to become similar to married couples over time, even if the initial decision to cohabit may have been only a small step beyond dating.

Conclusions

This study identified the characteristics of women that jointly affect the likelihood of experiencing an abortion and ending a romantic relationship. Such characteristics may include, for instance, personality, attitudes, and beliefs. Given that there was an elevated likelihood of obtaining an abortion around the time of a divorce, care should be taken in ensuring that women who face this difficult experience receive the family planning services and counselling they need. Overall, however, abortion rates in Finland are low compared to most other Western countries with liberal abortion legislation, indicating that the family planning health care system and sexuality education provided in schools cater satisfactorily to women’s needs.

References

Berg, Venla, Anna Rotkirch, Heini Väisänen, and Markus Jokela. 2013. ‘Personality Is Differentially Associated with Planned and Non-Planned Pregnancies’. Journal of Research in Personality 47 (4):296–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.01.010.

Ellison, Christopher G., Samuel Echevarría, and Brad Smith. 2005. ‘Religion and Abortion Attitudes Among U.S. Hispanics: Findings from the 1990 Latino National Political Survey*’. Social Science Quarterly 86 (1):192–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0038-4941.2005.00298.x.

Hess, Jennifer A., and Justin D. Rueb. 2005. ‘Attitudes toward Abortion, Religion, and Party Affiliation among College Students’. Current Psychology 24 (1):24–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-005-1002-0.

Jones, Rachel K., and Kathryn Kost. 2007. ‘Underreporting of Induced and Spontaneous Abortion in the United States: An Analysis of the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth’. Studies in Family Planning 38 (3):187–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00130.x.

Lillard, Lee A., and Linda J. Waite. 1993. ‘A Joint Model of Marital Childbearing and Marital Disruption’. Demography 30 (4):653–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061812.

Steele, Fiona, Constantinos Kallis, Harvey Goldstein, and Heather Joshi. 2005. ‘The Relationship between Childbearing and Transitions from Marriage and Cohabitation in Britain’. Demography 42 (4):647–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/4147333.

Väisänen, Heini. 2017. ‘The Timing of Abortions, Births, and Union Dissolutions in Finland’. Demographic Research 37 (28):889–916. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2017.37.28.