Well targeted policy measures can influence fertility even in times of intensive social and economic change. Analysing data from the Hungarian Generations and Gender Survey, Zsolt Spéder, Lívia Murinkó and Livia Sz. Oláh show that flat-rate cash support encouraged low educated two-child parents to have a third child, and tax-relief had a similar effect among the highly educated.

Arguments about the efficiency of family policies have often been challenged in the literature, and empirical results from cross-country comparisons are mixed or inconsistent (Gauthier 2007). Interest in policy effects is nonetheless considerable, and even increases in times of extremely low fertility. Hungary, like many other countries making the transition from state-socialism to capitalism, experienced radical institutional changes, periods of major economic decline but also of prosperity, and a rapid shift from early to late family formation (postponement) resulting in extremely low period fertility. At the same time, the family support system underwent radical reform. Formerly universal, it became means-tested in 1995, and then universal again in 1999, but was accompanied by large-scale tax measures. Discontinuities like these, despite substantial family-related government spending, are not generally believed to encourage fertility, which remained low in Hungary, at about 1.3 children per woman between 1999 and 2011, and is still below 1.5 today.

Two predictable measures within a complex but changing family support system

Two influential policy measures to support large families and encourage third births were introduced in Hungary in the 1990s. In 1993, during the most intensive period of socio-economic and institutional change, child-rearing support was introduced for parents with three or more children. It took the form of a monthly flat-rate cash benefit, paid from the third to the eighth birthday of the youngest child. A few years later, in 1999, a comprehensive tax relief system came into effect, mainly benefiting parents of three or more children with taxable income. While the former measure was designed above all to enhance the well-being of large, disadvantaged families and to ease transitional labour market difficulties, the latter was explicitly pronatalist.

These two measures form part of a comprehensive four-tier family policy system (Makay 2019), based on

- A guaranteed universal family allowance paid until a child’s 18th birthday;

- a parental leave scheme with two years of wage-related benefits and another year of flat-rate benefits;

- individual tax relief favouring large families;

- various forms of in-kind assistance, most specifically subsidized public childcare.

In 1999, in the middle of our study period, the cash and in-kind benefits provided to families in Hungary represented 3.13 per cent of GDP, a generous level (Thévenon 2011) relative to other OECD countries.

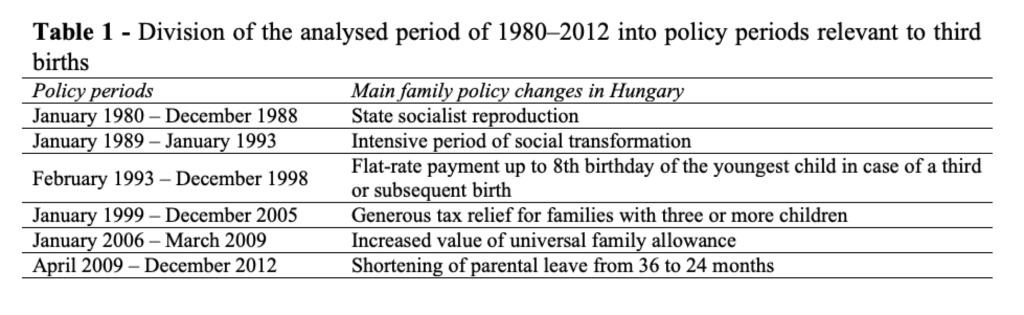

In our study on policy effects using event history analysis (Spéder et al. 2020) we assumed that any significant increase or decrease in third-birth risks (controlling for the effects of individual factors) was attributable to measures introduced at the beginning of a policy period. This analytical strategy has been successfully applied in other studies examining policy effects on fertility (e.g. Hoem et al. 2001), even if various other confounding factors in the same period may also have influenced birth risks. We differentiated between six relevant periods (see Table 1). The two dates marking the introduction of the above-mentioned measures were obvious milestones in the partitioning of the three decades studied.

Of course, various strata in a society may react differently to specific policies. For example, flat-rate and lump-sum support may primarily motivate lower-income groups, whereas tax relief may be of particular benefit to parents with medium or high income. We took this aspect into account in our research design, using education as a proxy for social status and income class.

Differential fertility effects

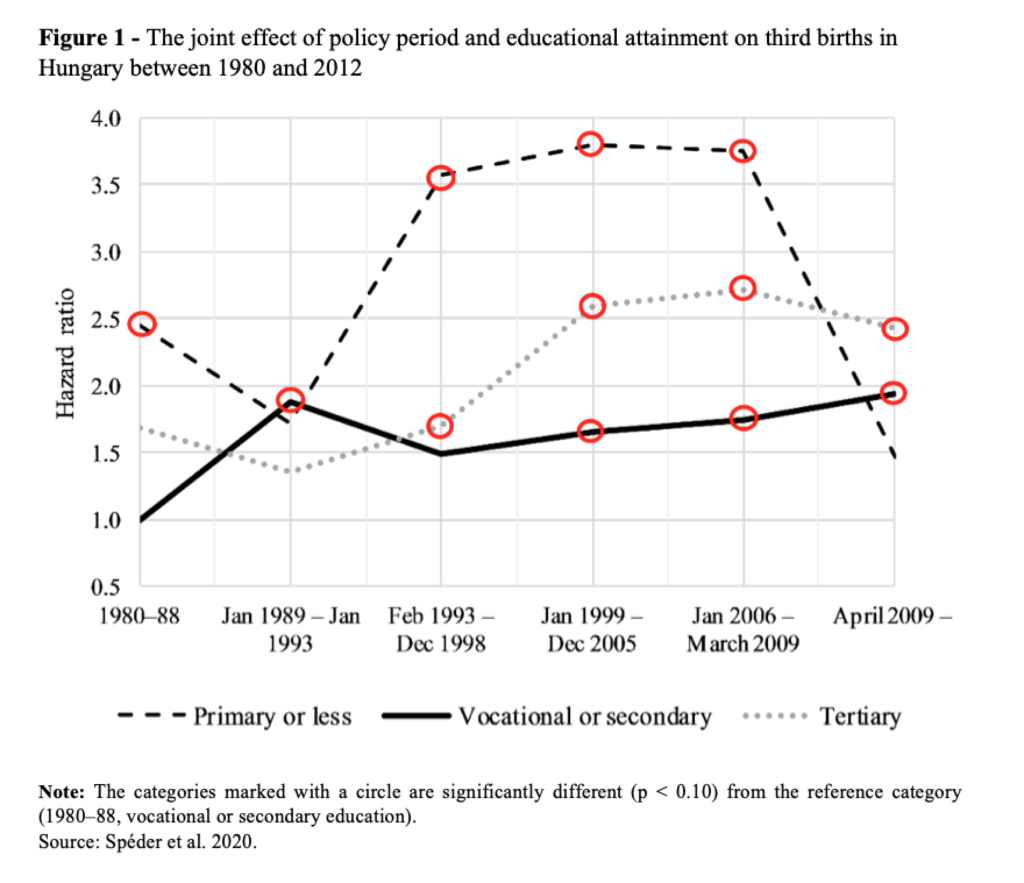

Figure 1 displays policy effects by level of education and period. People with a medium (vocational or secondary) education in 1980–88 are our reference category. The hazard ratios for various educational attainment categories during the periods are significantly different from the reference category, indicating clear but varied policy effects by educational level. Third birth risks of the low educated soared in 1993, when child-rearing support for stay-at-home mothers was introduced, and remained high during the years in which this support remained unchanged. For parents with tertiary education, instead, we see a pronounced increase in third birth intensity from 1999, when tax relief for large families was introduced and then generously upgraded. The high third-birth intensity with respect to the reference also remained significantly higher during the subsequent periods. The relative risk of a third birth also increased somewhat for parents with vocational or secondary education after 1998, although to a lesser degree.

Thus, our results show that flat-rate child-rearing support during prolonged parental leave motivated parents with lower socioeconomic status to have more children. The measure may even have protected them from some negative consequences of the economic transition such as unemployment, and to some extent from child poverty, ensuring societal recognition of ‘stay-at-home motherhood’ at the same time. The tax relief, in contrast, seems to have encouraged two-child parents with high educational attainment to have a third child, with little influence on parents with low socioeconomic status. The comprehensive tax relief may not only have stimulated third childbearing but also helped mothers to strengthen their labour market position, thereby raising family income to levels that were high enough to derive full benefit from the tax concessions offered.

Although the impact of these measures on overall Hungarian fertility remains low, in part because of the fertility postponement that characterizes younger generations, the predictability of the new measures and their sizeable financial scale produced a clear effect, with interesting subgroup differences.

Acknowledgement

Financial support to the authors via the Swedish Research Council grant to the Linnaeus Center on Social Policy and Family Dynamics in Europe, SPaDE (grant number 349-2007-8701), and to the first and second authors via the Hungarian Science Foundation under the grant ‘Families in Transition’ (K109397) are gratefully acknowledged.

References

Gauthier, A. H. 2007. The impact of family policies on fertility in industrialized countries: A review of the literature, Population Research and Policy Review 26(3): 323–346.

Hoem, J. M., A. Prskawetz and G. Neyer. 2001. Autonomy or conservative adjustment? The effect of public policies and educational attainment on third births in Austria, 1975–96, Population Studies 55(3): 249–261.

Makay, Zs. 2019. The family support system and female employment. In J. Monostori, P. Őri and Zs. Spéder (eds.), Demographic Portrait of Hungary 2018. Budapest: Hungarian Demographic Research Institute, 85–105.

Spéder, Zs., L. Murinkó and L. Sz. Oláh 2020. Cash support vs. tax incentives: The differential impact of policy interventions on third births in contemporary Hungary. Population Studies, 74(1), 39–54.

Thévenon, O. 2011. Family policies in OECD countries: A comparative analysis, Population and Development Review 37(1): 57–87.