Child loss continues to be a common life event for women in the Global South. Diego Alburez-Gutierrez documents a historic opportunity to close the gap between the South and the North in this respect. He also projects that ‘child death’ will increasingly refer to the death of an adult son or daughter.

Few people would question the saying that ‘no parent should have to bury a child.’ Child mortality has been low for so long in some parts of the world that the idea that children might die before their parents seems unnatural. Even in the Global North, however, things have not always been this way. For millennia, losing multiple children was the norm: in historical populations, parents usually lost about half of their children before they reached puberty (Volk and Atkinson 2013).

Conversely, in the Global South, despite remarkable progress in recent years, the death of a child, particularly a young one, continues to be a common life event for many parents.

A historic opportunity to reduce the gap between the Global South and North

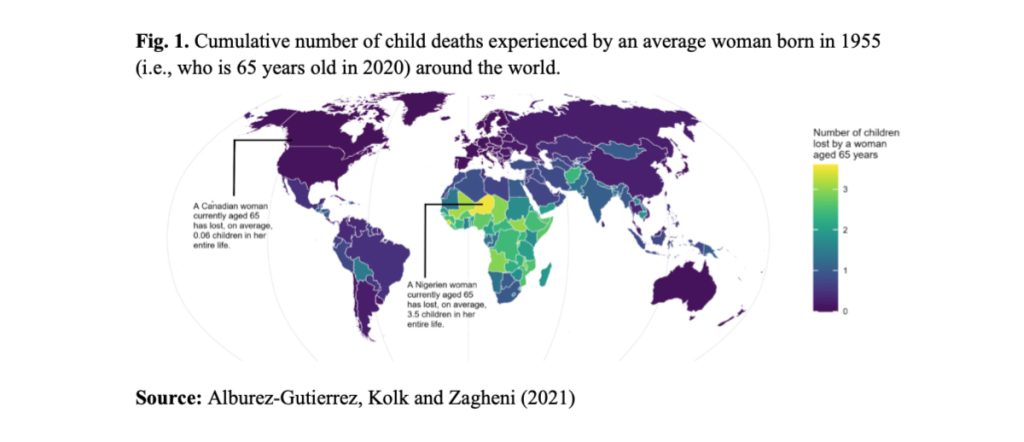

In a recent study, my co-authors and I illustrate the huge differences in terms of child loss suffered by mothers depending on their place of birth, with the Global South being particularly affected (Alburez-Gutierrez, Kolk and Zagheni 2021). For example, women born in 1955 in Niger experienced 73 times more child deaths during their working ages than women of the same cohort in Sweden. Figure 1 exemplifies these differences on a world map by showing the number of children that an average woman aged 65 years in 2020 has lost over her life course. Recent studies on the prevalence of maternal bereavement have found a similar pattern, showing that 79% of mothers in Niger have lost at least one child, compared to less than 1% of mothers in Sweden (Smith-Greenaway and Trinitapoli 2020, Smith-Greenaway et al. 2021).

The risk that women in a population will lose a child at some point of their life depends on the prevailing levels of fertility and mortality. In general terms, high fertility increases the likelihood of losing a child because more women have several children and are thus exposed to a higher risk of losing at least one. The risks are even higher if mortality levels are also high. Knowledge of past, present, and future demographic developments is crucial for characterizing global trends in child loss.

An overall favourable trend

Some of our findings are encouraging. We anticipate that the experience of child death will be increasingly uncommon among younger cohorts of women all around the world. In addition, we project that the gaps between women in countries of the Global North and countries of the Global South, currently very large, will shrink in the coming decades. Yet, some inequalities will persist. For example, the death of a young child will continue to be a distressing reality for many women in sub-Saharan Africa.

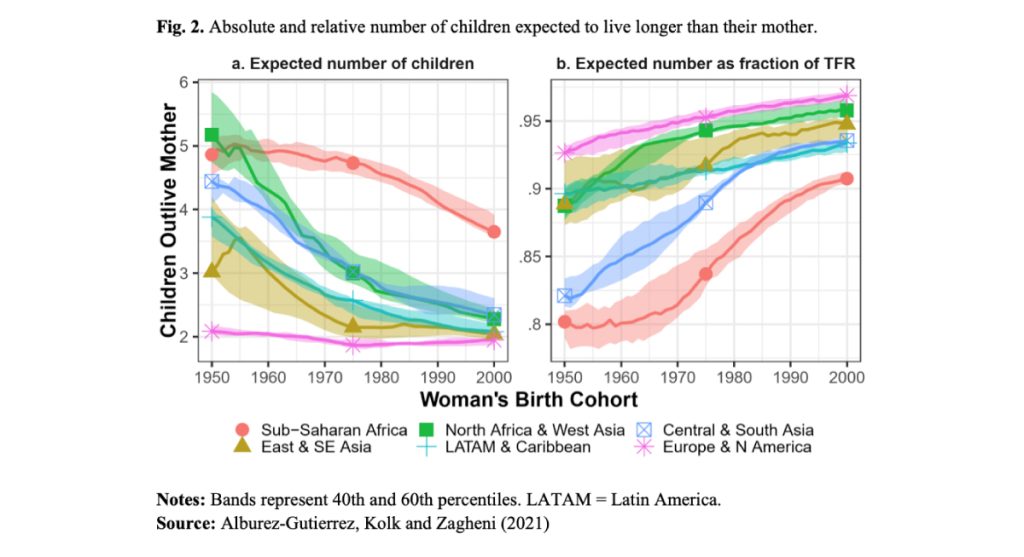

Figure 2 exemplifies these trends by focusing on the related phenomenon of child survival. On average, women born in 1950 can expect four of their children to live longer than themselves, while for women born in 2000 the global average will be about two (left panel). These estimates are largely driven by fertility levels, which are expected to converge to about 2.1 children per woman by the end of the century. A complementary measure is the fraction of children who are expected to outlive their mothers. The right panel of Figure 2 shows a global convergence of this relative measure of child survival. The share of offspring who will outlive their mothers will increase globally from 89% for the 1950 cohort of women to almost 95% for the 2000 cohort. The difference between the region with the highest survival (Europe and North America) and the region with the lowest survival (sub-Saharan Africa) will decline over this period from 15 to just 5 percentage points.

These trends have an unexpected and previously unrecognized effect: women born in 1985 or later will be more likely to lose an adult child (when they themselves are aged 65 years or over) than to lose a young child (before their own 50th birthday), reversing a long-standing global trend. We anticipate that “child death” will increasingly come to mean the death of adult offspring.

A call for support to bereaved parents

The loss of a child is a traumatic event that affects the mental and physical health of parents in general and of mothers in particular. Studies have linked child loss to depression, poor self-rated health, increased alcohol consumption and intimate partner violence. These effects are particularly pronounced in countries where bereaved parents have no recourse to counselling or any other institutional form of support. Our finding that parents will increasingly face the death of an adult child requires particular attention. This trend is worrying if mothers (and fathers, even if they are not explicitly considered in our paper) plan their lives around the expectation that their adult children will survive to support them in their older years. The consequences may be especially severe following the death of an only child, a growing risk for women (and parents) in countries with very low fertility. The situation is particularly ominous in settings that lack adequate institutional systems of old-age support.

References

Alburez-Gutierrez D., Kolk M., Zagheni E. (2021). “Women’s experience of child death: A global demographic perspective.” Demography. Advanced Publication. DOI: 10.1215/00703370-9420770

Smith-Greenaway E., Alburez-Gutierrez D., Trinitapoli J., Zagheni E. (2021) “The Global Burden of Maternal Bereavement: Indicators of the Cumulative Prevalence of Child Loss.” BMJ Global Health, 6:e004837. DOI:bmjgh-2020-004837.

Smith-Greenaway E., Trinitapoli J. (2020). Maternal cumulative prevalence measures of child mortality show heavy burden in sub-Saharan Africa. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117, 4027–4033.

Volk A.A., Atkinson J.A. (2013). Infant and child death in the human environment of evolutionary adaptation. Evolution and Human Behavior, 34, 182–192.