Generational overlap has mainly been studied for populations in the global North, but it affects care time demands on parents worldwide. Indeed, demographic ‘sandwiching’ is more prevalent in the global South, although is expected to decline by one-third between 1970 and 2040. These trends have important policy implications, says Diego Alburez-Gutierrez.

Is population aging mainly a concern for countries in the global North?

Population aging is often framed as a problem mainly affecting countries in the global North, where fertility and mortality are low. The European Commission Green Paper on Ageing (EC, 2021) aimed at identifying policies to tackle all aspects of this phenomenon. The document points up the changing proportion of working-age individuals in the population, echoing the view that measures like dependency ratios capture the main implications of population aging for societies.

However, contemporary demographic changes affect populations beyond dependency ratios. The Green Paper on Ageing itself also identifies “solidarity and responsibility between generationsˮ as an essential component of future policies to address population aging. This relates to the demographic concept of generational overlap, the degree to which members of different generations are alive at the same time (Grundy and Henretta, 2006). Overlapping generations are a universal phenomenon, but, with a few exceptions (de Lima, Tomás and Queiroz, 2015; Urdinola and Tobar, 2019), the phenomenon has been studied mainly in the global North.

Global trends of generational sandwiching

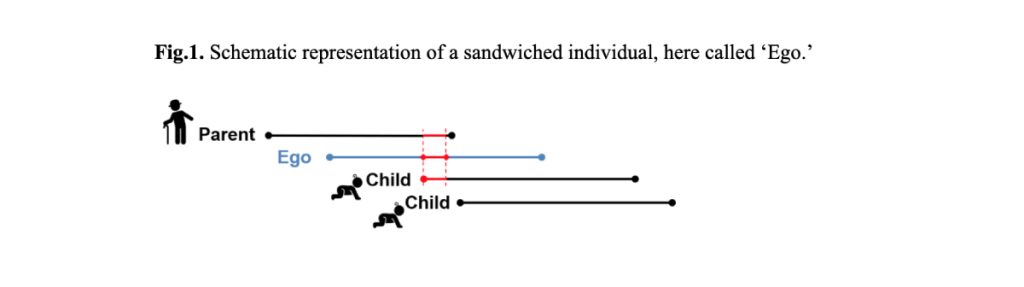

The Sandwich Generation refers to a particular type of generational overlap. The concept is not uniformly defined in the literature, making it difficult to study in an international comparative perspective. In a recent paper (Alburez, Zagheni and Mason, 2021), we use a standard demographic definition of generational “sandwichingˮ to study the phenomenon worldwide. Building on existing work (de Lima, Tomás and Queiroz, 2015), we consider individuals to be sandwiched if they have at least one young child (aged 15 years or less) and a parent or parent in-law who is expected to die within 5 years. This is exemplified in Figure 1, where the red segment in Ego’s lifeline represents the sandwiching period. Similarly, we consider individuals to be “grand-sandwichedˮ if they simultaneously have at least one young grandchild and a parent or parent-in-law who is expected to die within 5 years.

Armed with this definition, we estimated the prevalence of demographic (grand)sandwiching using a large number of demographic microsimulations based on demographic data from the United Nations’ 2019 revision of World Population Prospects. The simulated microdata allowed us to identify and quantify the periods in which parents around the world find themselves sandwiched between generations. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first overview of the degree to which parents face simultaneous care-time demands from multiple generations around the world.

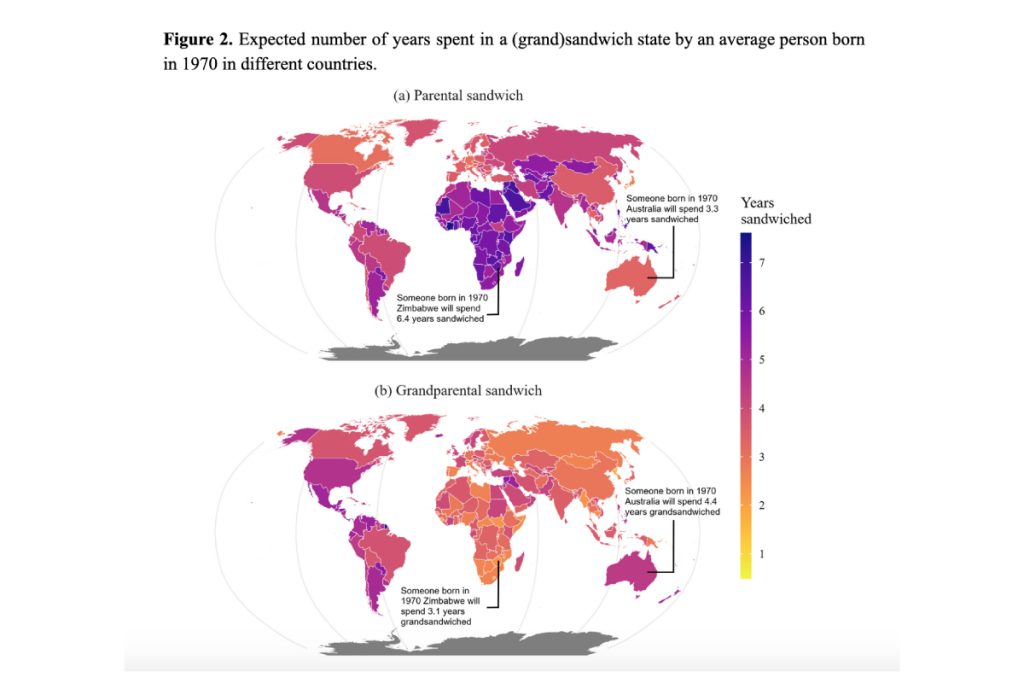

Perhaps the main finding is that the Sandwich Generation is less prevalent in the global North than in the global South, where parents are also more likely to spend longer periods in this state ‒ a surprising finding given that the life expectancy of parents is lower in the global South than in the North. Figure 2 exemplifies these trends by showing the number of years that a person born in 1970 can expect to spend (grand)sandwiched.

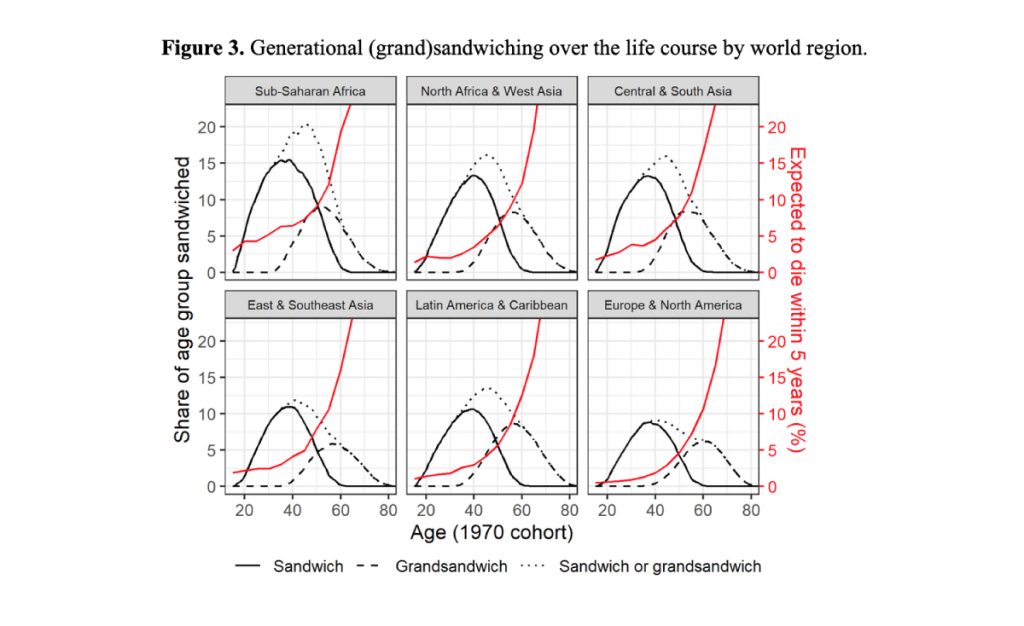

The study also provides novel evidence on the incidence of demographic sandwiching over the life course. Figure 3 shows the ages at which care-time demands are expected to peak in different regions, a period that Zannella et al. have called the “rush hour of lifeˮ (2019). The burden of generational (grand)sandwiching throughout their lives is greatest for individuals born in Sub-Saharan Africa and smallest for those born in Europe and North America. This contradicts the received wisdom that parents in the global North face the largest burden of sandwiching as a result of more widespread population aging.

Implications of generational sandwiching

A continued focus on the generally wealthy countries of the global North has limited our understanding of the demographic dynamics that drive generational overlap on a planetary scale. Global studies allow us to situate phenomena in a comparative perspective. The finding that parents in the South face a heavier burden of sandwiching is especially relevant when we consider that they often also lack access to adequate systems of old-age support (such as pensions) and institutional childcare.

These trends have implications for the future of our societies. In our study, we project that people will face fewer demands to provide informal care to family members in the future. This may be a welcome development for over-burdened parents. At the same time, increased availability of grandparents can help to ease time constraints for parents in low- and middle-income countries. Generational overlap does not need to be a burden on individuals and families.

References

Alburez‐Gutierrez, D., Mason, C., and Zagheni, E. (2021). The “Sandwich Generation” Revisited: Global Demographic Drivers of Care Time Demands. Population and Development Review. Avanced publication.

Grundy, E. and Henretta, J.C. (2006). Between elderly parents and adult children: a new look at the intergenerational care provided by the ‘sandwich generation’. Ageing and Society 26(5):707–722.

de Lima, E.E.C., Tomás, M.C., and Queiroz, B.L. (2015). The sandwich generation in Brazil: demographic determinants and implications. Revista Latinoamericana de Población 9(16):59–73.

Urdinola, B. Piedad, and Jorge A. Tovar, eds. 2019. Time Use and Transfers in the Americas: Producing, Consuming, and Sharing Time Across Generations and Genders. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Zannella, M., Hammer, B., Prskawetz, A., and Sambt, J. (2019). A Quantitative Assessment of the Rush Hour of Life in Austria, Italy and Slovenia. European Journal of Population 35(4):751–776.

EC (2021). Green Paper on Ageing. European Commission.